Each year, firms invest millions of dollars in diversity programs aimed at increasing the representation and advancement of women and racial minorities. Sociologists have found that some of these programs work, and some do more harm than good. One key ingredient in whether diversity programs improve, or worsen, the representation of women and racial minorities is if these initiatives are supported by employees. Programs that are viewed positively by workers are more likely to produce the intended results, while those that are resisted may result in a backlash and actually make conditions worse for underrepresented groups.

In a recent study, we explored how people feel about different types of diversity programs and why they feel the way they do. We used data from a TESS (Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences) survey that asked nearly 2,000 working individuals whether they supported eight different diversity policies. The design of the survey allowed us to see if support differed based on whether policies are aimed at women or racial minorities, as well as if support differed based on if the policies were justified to improve diversity, address discrimination, or if no justification is given.

How do people feel about diversity policies?

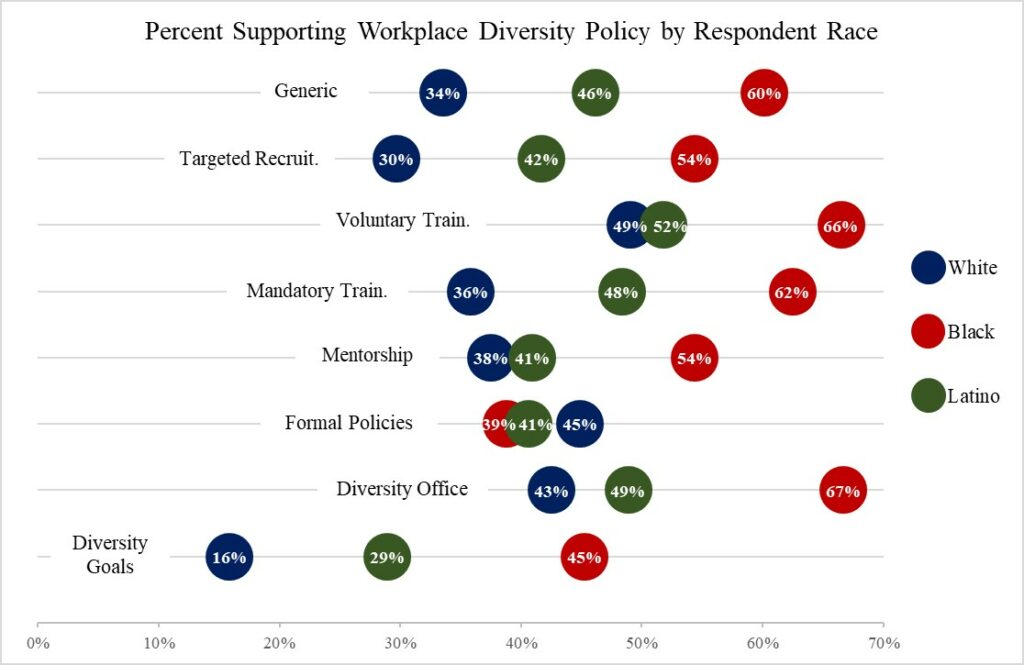

In general, workers are most supportive of voluntary training and the establishment of a diversity office. This is good news, since these programs have been found to be among the most effective at improving the representation of women and racial minorities.

The bad news, however, is that white workers are less supportive of workplace diversity initiatives than black and Latino workers. A majority of whites expressed opposition to all of the types of policies we examined. In contrast, the majority of black workers supported six of the eight policies, while about half of Latino workers expressed support for four of the eight policies.

In addition to having the lowest overall levels of support, white workers were also more strongly opposed to policies aimed at improving the representation of racial minorities than they were toward those directed towards improving the representation of women.

While white, black, and Latino workers mostly differed in how they felt about diversity policies, there was one commonality between them: Diversity programs received more support when framed as needed to address discrimination than when justified to improve diversity or when no justification was given. This provides evidence that the most effective way to frame diversity policies is to direct focus towards social problems such as discrimination.

Why do people feel the way they do about diversity policies?

The fact that the majority of white workers oppose diversity programs presents a major challenge for human resource managers and diversity officers aiming to implement successful initiatives. In order to understand the factors contributing to people’s attitudes about diversity programs, we also examined how individuals’ beliefs about gender/racial inequality are associated with their opinions about diversity policies.

More than any other factor, workers who felt that discrimination causes gender/racial inequality showed the highest levels of support for diversity policies. This was true across worker race and gender. We also found that a major reason why women and non-whites show higher levels of support than men and whites is because they are more likely to believe discrimination causes inequality.

In other words, much opposition to diversity programs comes from those who do not think discrimination is to blame for racial/gender disparities in U.S. society. For the most part, these individuals are white men, and this is a major reason why this group has the lowest levels of support for diversity programs.

Lessons for successful diversity initiatives

We now know how people feel about diversity policies and how their beliefs about the sources of inequality are associated with those opinions. Previous work on individuals’ inequality beliefs has shown that these schemas can also shape workers’ perceptions around workplace climate. We also know from other research that some diversity policies, such as accountability goals, mentorship programs, and diversity offices, are effective at improving the representation of women and racial minorities, while others, such as mandatory training and grievance systems, can do more harm than good.

So, what can we do with this information to improve the effectiveness of our diversity initiatives and, ultimately, create more equitable workplaces?

Our research identifies some opportunities. We suggest that voluntary training programs that use an engaged curriculum focused on issues of workplace inequality and discrimination will not only achieve immediate benefits, but will also help create more widespread support for other far-reaching diversity policies, such as the establishment of accountability goals or diversity task forces. These types of trainings promote conversations about social issues relating to race, class, and gender and involve workers in designing effective solutions.

Beginning with a focus on voluntary training may not seem like the most ambitious approach to diversity initiatives. But it is an important first step for workplaces just implementing diversity programs or those where resistance is high. In these settings, focusing on these types of small wins can be an effective approach to achieving long-term equity transformation.

Whatever policies are adopted, our research indicates that managers should not shy away from critical issues around social inequality. In our study, policies framed as needed to address discrimination received higher levels of support than alternative framings focused less on social inequality. Workplaces can be engines of equitable change or vehicles in the reproduction of inequality. When made aware of issues around discrimination, our research suggests that workers are motivated to ensure they contribute to equitable environments.

Diversity policies have the potential to improve labor force equity and address patterns of stratification more broadly. Yet, these initiatives can sometimes do more harm than good. By using the most popular programs to educate workers on social inequality and discrimination, managers will be well-positioned to garner broader support for issues around diversity/inclusion and create more equitable workplaces.

Read more

Scarborough, William J., Danny L. Lambouths III, Allyson L. Holbrook. 2019. “Support of workplace diversity policies: The role of race, gender, and beliefs about inequality.” Social Science Research 79: 194-210.

For a free, pre-publication version of the article, click here.

Image: Arek Socha via pixabay (CC0)

No Comments