“Get yourself a good government job!” This familiar refrain originates in the Black community, for whom public employment offers a rare respite from the inequities of the private sector labor market. Government jobs are in fact good for many groups. The pay, status, and rewards of African-American, female, and disabled public employees are closer to that of their white, male, and non-disabled colleagues, even when accounting for public-private differences in occupation and education. Recent attacks on public sector unions, moreover, are in part the result of prejudice against these groups.

Yet the public sector did not always protect African Americans and others. When Swedish economist and sociologist Gunnar Myrdal visited the United States in the 1930s and 1940s, he could still describe the “tenuous presence of Blacks in public employment.” This precariousness was a legacy of the Woodrow Wilson presidency which introduced segregation and discrimination into civil service hiring practices.

In a recently published paper, we find that unionized Black Americans played a crucial role in improving the quality and pay of public employment. To be sure, large structural changes to the U.S. economy facilitated these improvements, but they did not guarantee them. The “Great Migration” of African Americans from Southern states to Northern cities, the expansion of public sector collective bargaining rights, and the tendency of government to “model” fair employment set the stage for the path-breaking activism of Black public employees in the 1960s.

Pay schedules improve pay parity

To demonstrate, we trace the political history of the Federal Wage System (FWS). This pay schedule regulates wages for blue-collar federal employees, who are often also Black. Wage schedules are critical policy tools for pay parity. They offer workers transparent wage benchmarks and level the overall distribution of earnings — both across an industry, and sometimes even across the macroeconomy.

Although many public employees benefit from pay scales, the FWS was a relative latecomer to federal pay-setting. Enacted in 1972, decades after the schedules for white-collar (and usually White) workers, the FWS now sets pay for federal blue-collar workers by determining the local prevailing wage in comparable private sector occupations. Earnings and protections under the FWS can be more attractive to Black workers than those of the private sector, where racial labor market disparities are sharper.

Of particular note is how the FWS protects workers in rural labor markets. In Alabama, for example, Black-White wage differences are smaller for federal blue-collar workers than clerical and white-collar workers. Here, FWS employees earn the prevailing wage afforded to private sector employees in metropolitan areas, but in areas with lower cost of living.

Before the 1960s, racial pay parity was not a priority for the public sector

The initial reluctance of public employers and unions to support racial pay parity helps explain the delayed enactment of the FWS. Federal initiatives to address Black-White earnings were confined to the higher rungs of government service expressed in executive attempts at affirmative action. These top-down attempts to improve the image of government leadership in fact had little substance for the majority of Black public employees– and policy-makers barely consulted Black interest groups for advice.

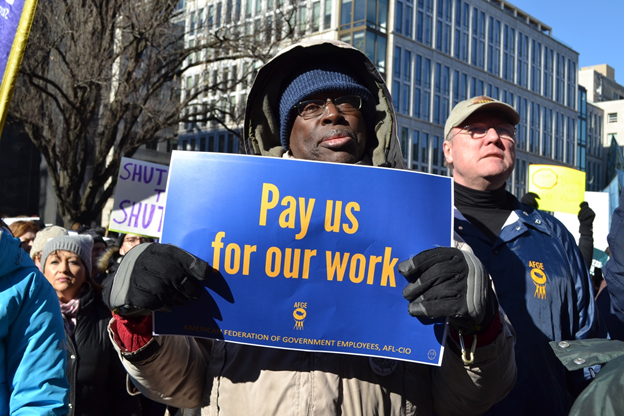

Racial equity was not a genuine priority for federal trade unions, either. In our research, we found only one attempt by the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) to promote the rights of its African American members during this period: a Bill of Rights drafted in 1938 “for the protection of some 8,000 Negroes employed by the Federal and District of Columbia governments.” These plans soon evaporated bereft of the union’s support.

Organized Black government employees pivoted union attention to racial issues, and changed pay policy

From the 1960s onward, however, the expansion of the federal government, public sector unionization, and the Civil Rights Movement enabled the growing number of low-wage, unionized, and urban African-American employees to demand better working conditions for blue-collar workers. Not all public unions agreed to represent these workers – but for those that did, like the AFGE, the results were transformative.

A race-conscious protest vote by AFGE’s Black members in 1962 was the first step toward changing the union’s national level strategy on race and blue-collar wages. That year, the group opposed the election of John Griner, a white member, as union president, but ultimately agreed to accept Griner’s leadership in exchange for several concessions – including, critically, the union-wide adoption of Black and blue-collar policy issues.

The Black members’ support paid off. By 1967, the AFGE had adopted a new policy goal: to reform the non-statutory method of setting pay for blue-collar federal employees (the coordinated Federal Wage System) through congressional legislation. Its efforts, combined with the continued pressure of Black protest at union conventions, propelled the legislative campaign forward.

“We are being faced with a grave situation,” President Griner implored to legislators over the protestations of federal administrators, “Militancy among this group of employees is on the increase. All they are asking for is justice and equity. I say to you, they are not getting justice and equity.”

A bill passed Congress on December 15, 1970. Yet a veto followed two weeks later. Hiding behind a classic monetary policy trope, President Nixon asserted that the “fires of inflation are fueled” when the rising federal wages compelled private wages to do the same. Increasing spending, he also argued, would lead to job cuts.

A presidential veto, though, did not stop the union’s legislative momentum. To avoid a second veto, and as proof of his commitment to the legislation, Griner made an arrangement. The labor leader gave his personal endorsement of Nixon’s bid for a second term in exchange for the President’s signature of a second – and more progressive – bill. (Griner did not go so far, however, as to tender the union’s formal support for a Republican campaign.) In an about-face that startled observers, the President signed Public Law 92-392 on August 19, 1972.

The enactment of the Federal Wage System undoubtedly improved the quality of blue-collar government work. Although deficiencies remain, the advocacy of unionized Black, blue-collars workers was fundamental to this landmark reform. The achievement demonstrated both the power of mobilized African American workers as a category and the significance of public sector employment in delivering closer to equitable wage parities than experienced in the private sector.

Read more

Isabel M. Perera and Desmond King. “Racial Pay Parity in the Public Sector: The Overlooked Role of Employee Mobilization” in Politics & Society, 2020. For a free, pre-publication version of the article, click here.

Image: AFGE via Flickr CC BY 2.0

No Comments