Most popular discourse on “returns to college” tends to assume—implicitly or explicitly—that adult class location is largely a result of individual earnings that flow from investments in education.

Recently, we published a qualitative longitudinal study of social mobility among a cohort of college-educated white women in the American Journal of Sociology. We followed 45 women who started college on the same residence hall at a flagship public university for 12 years, with a final wave of data collection at age 30.

We show that social class location over time was “sticky,” in that both upward and downward mobility were limited. The heavy hand of social class in shaping both marital patterns and the transfer of wealth accounts for the persistence of class position across generations.

Class origins and class destinations

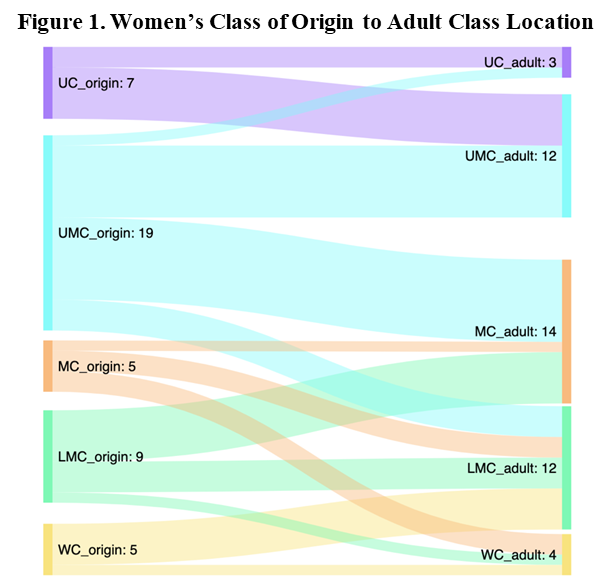

Figure 1 offers a visual representation of flows from social class of origin into adult class locations at age 30.

Among this cohort of adult white women, the upper class (UC) and upper-middle class (UMC) are composed entirely of those who grew up in privileged families. Fifty-eight percent of women who started in privileged social class positions (i.e., either upper-middle or upper class) remained so as adults. Women from privileged families typically did not fall further than the middle class (MC), and none landed in the working class (WC). The four women who experienced the steepest downward mobility were still relatively protected in the lower-middle class (LMC).

Of those from less privileged families, 47% were upwardly mobile. The highest they reached, though, was into the middle class. Strikingly, not a single woman from a less privileged family broke into a privileged location by age 30. Just over a quarter (26%) from less privileged families reproduced their class position—a potentially disappointing outcome for those seeking to improve life circumstances. Another 26% even experienced downward mobility relative to their parents’ midcareer class locations.

College was not the “great equalizer” for these women. Why didn’t less privileged white women see a greater boost from their college attendance? And why didn’t privileged white women who were downwardly mobile fall further?

Most American women, even college-educated white women, can’t make it into the upper-middle class based on their own earnings

Women’s earnings alone did not reveal much about their class location at age 30. A majority of employed women in our sample (60%, 25 of 42) were modestly compensated, earning between $40,000 and $74,000 in traditionally feminine occupations, mostly in education, healthcare, and human resources. Very few—irrespective of class background—were situated to support an upper-middle-class lifestyle on their own salaries at age 30.

This is consistent with broader patterns. Census data indicate that college-educated men have a much better chance of earning enough to break into the privileged classes. Despite completing college at higher rates than men, women still experience occupational segregation, which plays a key role in the gender pay gap.

Thus, if and whom women marry matters a lot for adult women’s class location

Of the 15 women who arrived in privileged locations as adults, all but three (80%) married, and three-fourths of those who did marry were partnered with men making at least $100,000. These men were also almost exclusively from privileged families. In contrast, of the 30 women who landed in the middle, lower-middle or working class, 21 (70%) married; only four were married to men making more than $100,000, and none married men making $500,000 or more.

More often than not, privileged white women in our sample married from deep within networks to privileged white men connected to their hometowns and whose college friendship groups overlapped with theirs. For less professionally ambitious women, this was achieved by identifying marital prospects early and then watching and waiting, cushioned by family support as they socialized with class-appropriate white men likely to move into lucrative positions. In contrast, more professionally ambitious women tracked alongside similarly advantaged men who were academically and professionally engaged, leading to future matches.

Women from less privileged families did not know wealthy men through their communities of origin. Working in low-paying, highly feminized fields also meant that, in most cases, they did not encounter high-earning partners through work. Fellow teachers, for instance, made similar salaries. These women had to move entirely outside of their networks to meet high-earning partners. Doing so required intentionality, willingness to endure the discomfort of leaving behind family and friends, and sufficient resources to move. High-risk mobility moves were not possible or desirable for many women.

The women in this study are not unique. Marriage still matters tremendously for women’s economic welfare, and it is the primary way women access upper positions in the stratification order.

Direct and indirect transfer of wealth from one generation to the next reproduces privilege and buffers downward mobility

Among the 15 women who arrived at privileged locations by age 30, all but two (87%) were recipients of ongoing transfers from their families (that is, continuous support during and after college) or bridge support (in other words, assistance during and in the transition out of college). By contrast, among the 30 women who were in the middle, lower-middle or lower class at age 30, only six received bridge support and one received ongoing support (23% combined).

Multigenerational transfers often occurred around life transitions—such as assisting with a move to a new city for employment, setting up an apartment, and purchasing transportation; paying for weddings, down payments, furniture, and interior designers; and covering educational expenses, ranging from childcare to graduate education. Transfers were often substantial enough that women’s adult class location could not be accurately described without taking these exchanges into account.

They also provided a compensatory safety net, protecting women from substantial downward mobility. For instance, one woman from an upper-class family received annual $8,000 checks from her mother, providing a much-needed cushion for a young couple with relatively low earning power. Such investments made it possible for women from privileged backgrounds to reach desired milestones of adult life (for example, home ownership, marriage, childbearing, and saving for retirement) earlier, and in much greater comfort, than others.

The cumulative nature of disadvantage made it difficult for white women from less privileged families to be upwardly mobile beyond the middle class, resembling what others have described as the “class ceiling.” Sometimes even two high salaries could not compensate for the debt that upwardly mobile women acquired in college—particularly if their partners also brought debt into the marriage.

Thus, consistent with research on the cumulative nature of inequality across generations, transfers play a central role in understanding adult class location.

Research focused on college as the “great equalizer” tends not to consider debt accrued during college and graduate school, ongoing support from parents, or marriage to similar others. Yet, these factors far outweighed women’s own earnings in shaping their class location at age 30. Had we interviewed a more racially diverse sample, differences in family wealth and marital patterns would likely have further exacerbated the stickiness of social class. We encourage scholars to think holistically about how education, earnings, marriage, and familial transfers interplay to shape adult class location.

Read more

Laura Hamilton and Elizabeth A. Armstrong. “Parents, Partners, and Professions: Reproduction and Mobility in a Cohort of College Women” in American Journal of Sociology 2021.

image: Herobrine via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

No Comments