Neoliberalism has profoundly transformed industrial relations systems—most notably, the implementation of pro-business labor policies aiming at decentralizing collective bargaining and restricting unions’ bargaining power.

In the last decades, neoliberalism has been publicly contested by labor unions and social movements across the globe. However, neoliberal labor policies have proven resilient against reform. In most countries progressive governments have been unable to implement policies to restore the institutional power resources unions used to have during the “golden age” of welfare capitalism.

Why is it so difficult to reform neoliberal, pro-business labor laws? How, in the context of highly globalized societies, can workers overcome the constraints progressive governments face in promoting pro-labor policies? How, in these contexts, can organized labor influence the policymaking process?

In my book Building Power to Shape Labor Policy, I address these questions through an explanation that emphasizes class-based collective action and power. Existing literature on policy reform offers explanations that stress government resolve to pursue reforms, emphasize the effects of authoritarian legacies (i.e., institutions inherited from past authoritarian regimes), and—as theorized in the traditional Power Resource Approach (PRA)—explanations that focus on how the linkages between labor and center-left ruling parties shape policy outcomes.

While not denying the importance of these variables, I contend that they must be understood together with the processes through which workers and capitalists organize to influence the policymaking process. In other words, I extend the traditional PRA and propose a relational model of class power that stresses the central importance of working-class and capitalist associational power. By associational power, I mean the type of power workers or employers develop through the formation of collective associations such as unions and employer associations. Therefore, studying associational power is crucial for developing an empirical analysis of the balance of power between workers and capitalists. This analysis of class power explains why neoliberal labor laws are so resistant to change.

In the book, I focus on the case of Chile where a neoliberal labor law was established as early as 1979, under the right-wing dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Despite their anti-union orientation, the central aspects of the1979 laws have remained intact throughout the democratic period.

Since Chile returned to democracy in 1990, all center-left administrations have discussed the need to reform the labor law, and many of them have proposed bills to amend it. However, while improving the protection of some individual labor rights, these reforms have failed to repeal the central pillars of the Pinochet legislation (e.g., the provisions that restrict collective bargaining to the level of the individual enterprise). As a result, despite Chile’s successful transition to democracy, labor’s demand for the repealing of the Pinochet legislation has not yet been met.

An analysis of Chile allows me to demonstrate that pro-labor reforms have failed because, despite the existence of ties between policymakers and labor leaders, Chile’s largest confederation (the Central Confederation of Workers, CUT) has been unable to build up associational power to influence the legislative process. Since the early 1990s, the CUT has been incapable of overcoming the political and strategic disputes that have divided the Chilean labor movement and undermined its collective power—e.g., most notably, in periods of center left rule, disputes between conciliatory (“pro- governments”) and militant factions.

In Chile these disputes have had particularly detrimental effects for labor power. They have increased labor fragmentation and weakness, especially when center-left parties in the government show little interest in responding to workers’ demands.

On the other hand, the Chilean business class has successfully mobilized associational power to oppose any attempt to reform the labor law (especially, collective labor law). In contrast to the CUT, the multi-sectoral association of employers, the Confederation of Production and Commerce (CPC), has successfully developed employer associational power through organizational structures that facilitate consensus among the sectoral associations that form its membership. In doing so, the CPC has forged strong capitalist class solidarity and consensus regarding the strategies to confront reformist governments.

Strong capitalist associational power explains why Chilean employers have been so successful at defending the continuity of the 1979 labor legislation. Additionally, employers’ associational power is crucial for understanding how businesses influenced the policy-making process in the mid-2010s, when several political factors that reinforced business power in previous decades (e.g., strong conservative parties with a veto power in Congress) had been downplayed.

Does this mean that we should abandon any hope of reforming neoliberal labor law? Of course not. Argentina and Uruguay, in contrast to Chile offer hopeful examples. In these two countries, progressive governments successfully implemented pro-labor reforms in the 2000s. Here, pro-labor reforms were more successful because the balance of power was more favorable for the working class. In Argentina and Uruguay, labor confederations built stronger associational power in the decade prior to the labor reforms. This enabled them to play a more active and influential role in the reform processes carried out by center-left governments throughout the 2000s. In contrast, in both countries, employers were unable to successfully build and mobilize associational power. This significantly undermined their capacity to influence the legislative processes and, more generally, their power to oppose the governments’ reformist agenda.

The evidence of Argentina and Uruguay reinforce, I argue, the implications of my in-depth case study of Chile. It demonstrates that partisan linkages are beneficial for labor—i.e., they lead to more protective labor policy—not only when party-union linkages are strong, but also when unions have the capacity to mobilize associational power independently from political parties. Similarly, the evidence reinforces the importance of extending the concept of associational power to analyze capitalist collective action and power. This extension of the concept enables me to show how, both in Argentina and Uruguay, employers’ weak associational power allowed the reformist governments to carry out legislative reforms without having to face significant opposition from organized business.

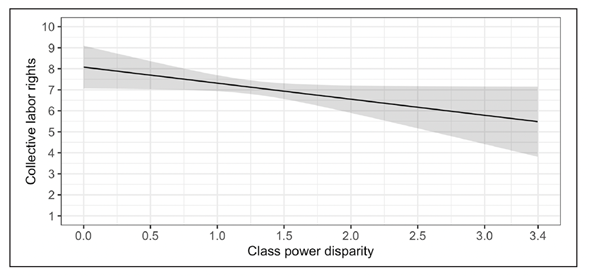

In another study, I examined quantitative data from 78 countries. Consistent with the above-mentioned argument, I found that the disparity of power between classes is negatively correlated with the degree of protection and extension of collective labor rights.

Figure 1. Relationship between class power disparity and collective labor rights (78 countries)

All in all, the main implications of my argument are two. First, the study of labor reforms aimed at extending workers’ rights requires examining not only the linkages between unions and center-left parties in power (as the traditional PRA does) but also how unions and employer associations mobilize associational power to influence the policymaking process. This implies dedicating more time to the study of business power and adopting a relational view of class power.

Second, the working class can successfully influence the policymaking process by developing autonomous associational power to establish a more symmetrical relationship with left-wing parties (i.e., a relationship in which parties can defend working-class interests in the legislature without sacrificing labor autonomy). When this occurs, union-party linkages can truly become an effective source of leverage for the working class in neoliberal society.

Read more

Pérez Ahumada, P. (2023). Building Power to Shape Labor Policy: Unions, Employer Associations, and Reform in Neoliberal Chile. Pittsburgh, PA: The University of Pittsburgh Press.

For a free version of the article cited, email the author at: pabloperez@uchile.cl