Job satisfaction matters. Of course, everyone would like to be happy with their work. But beyond that, scholars have also shown that job satisfaction is crucial for workers’ mental wellbeing and physical health, on the one hand, and important for employee performance and retention, on the other hand.

Job satisfaction matters. Of course, everyone would like to be happy with their work. But beyond that, scholars have also shown that job satisfaction is crucial for workers’ mental wellbeing and physical health, on the one hand, and important for employee performance and retention, on the other hand.

When we think about job satisfaction, we usually think about things like wages, office culture, or opportunities for self-fulfillment. But job satisfaction has another side to it: does your job make you feel like a good person?

Workers who think their job is meaningful are more likely to have job satisfaction. In particular, workers who think their jobs help others are more likely to report being satisfied with their jobs. In other words, you’re more likely to stay with your job if you think you’re helping others.

In that case, we might expect people who thought they were not helping to leave their jobs, assuming they had the means to do so. After all, people tend to avoid stigmatizing situations when possible—and doing unhelpful or harmful work is usually morally stigmatizing.

Which begs the question: why do admen and adwomen stay in their industry, when it’s generally viewed so negatively?

The stigma of the advertising industry

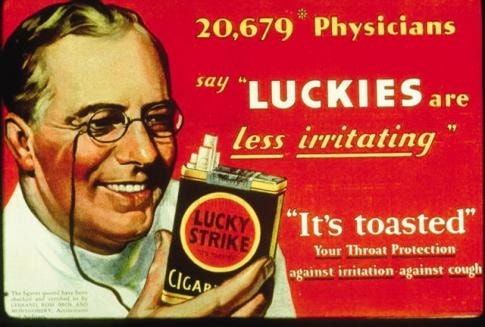

Advertising isn’t exactly a morally reputable profession.

Between the critical scholarship and op-eds on why advertising is evil, and the popular media representations of corrupt advertising executives (Mad Men being the most popular contemporary example), the industry has a clear social stigma as morally corrupt.

That moral stigma shows up in annual Gallup polls, where American are asked how they would rate “the honesty and ethical standards” of people in different fields. Year after year, advertising practitioners come in around the bottom of that list, right along with members of congress, lobbyists, and car salespeople.

Advertising professionals aren’t oblivious to this moral stigma. In his 1998 book, Truth, Lies, and Advertising, Jon Steel comically wrote to his peers: “I would thus like to suggest that all advertising people reading this should pause for a moment, raise their eyes to the heavens, and give thanks for the very existence of car salesmen”—the only profession to rank lower in the Gallup poll at the time of writing.

Despite the negative connotations attached to their profession, advertising agencies employ roughly 200,000 people in the United States alone—a number that has been rising since January 2010. For the vast majority, these are people who certainly have other opportunities to work in less stigmatized fields.

Let’s assume most of the 200,000 people working in advertising agencies are not morally bankrupt. In that case, how do they justify the moral worth of the work they do every day?

We explored this question in a recent study of three advertising agencies. While our original research questions had been about the work advertising professionals do more generally, we found in interviews that these professionals brought up issues of morality, unprompted—so we took the opportunity to explore how they thought about the moral worth of their work.

Narrating moral worth in advertising

Through the first author’s field observations and interviews, we found that advertising practitioners justified the moral worth of their work through narratives that tied their work to some conception of the common good, emphasizing the good service they believe advertising can provide to society. These narratives helped admen and adwomen frame advertising work as a morally worthy endeavor.

The narratives we heard weren’t simply random, ad hoc justifications. To the contrary, three particularly prevalent narratives emerged through our analysis: the account-driven narrative, the creative-driven narrative, and the strategy-driven narrative.

These three narratives roughly correlate to three primary departments of modern advertising agencies: account services, which serves as a liaison between the client and the agency; creative services, which comes up with the concepts, images, and words for campaigns; and account planning, which handles consumer research and develops strategies for campaigns.

In the account-driven narrative, advertising practitioners frame themselves as experts, using their expertise to care for clients, helping their clients realize their own goals. With this narrative, agency employees could compare themselves to doctors, hired to help sick brands or companies get better. As one creative-director-turned-CEO put it:

“I see our role as doctors, whose brands are unhealthy, they have problems, and they need someone to be honest with them. Generally speaking, we think we are fighting with them, but you know, a doctor takes a Hippocratic oath, and you need to tell them that this is the problem, and you’ve got to face those problems. And I think that changes the dynamic, when you really want to see the true beauty inside a brand or company, and you want to share that with the world in an effort to make them more successful. And you are trying to create something that will last and that will truly solve their problems.”

In the creative-driven narrative, agency employees frame their work as a process of creating beautiful, thought-provoking, or motivational objects for society. In other words, they framed making advertising as making art. While clients might get in the way of this by refusing to sign off on truly creative, inspiring work, the intention to make something valuable for society justified the moral worth of the work.

In the strategy-driven narrative, agency employees frame their work as consumer-centric, helping consumers find good brands that improve their lives. Through empathetically understanding specific groups consumers, advertising practitioners could do morally good work. As the president of one agency put it:

I get to come to work every day and help consumers find products and services that will make their lives better. That is what it really comes down to, right? So whether it’s a new insurance company, or it’s a new brand of soda-pop, or whatever it is that they haven’t discovered before that makes their life more enjoyable or better in some way—that is really what we do, and that is pretty cool to me. I think that that’s not a bad thing.”

With the account-driven narrative, employees at one agency justified working on tobacco (a largely unpopular and stigmatizing product) by pointing out how they provided the clients with an excellent level of service in a tough category. With the creative-driven narrative, employees justified working on tobacco by explaining how this client let them do some of their most interesting, creative work. And with the strategy-driven narrative, employees justified working on tobacco by explaining how their work helped a very particular demographic understand what kinds of options they had in the marketplace.

These narratives were not the only ones for justifying the moral worth of advertising work. We also found a few, lesser-used narratives, such as how working to support the agency itself or to a particular team showed loyalty, or how advertising in general helped support the overall economy. However, the three narratives we outlined—ones tied to consistent reference points in work activities—were the most prominent.

So what?

While it’s hardly surprising that a stigmatized community would have ways to justify its moral worth, our study highlights how important common narratives are in that process. Narratives help frame the chaos of daily life, and the way events are framed can dramatically influence how people understand and respond to those events. Common narratives offer communities particular ways to frame their activities as morally justified.

While much of the previous literature on responses to collective stigmatization has focused on race- and class-based stigma, we highlight professional communities as an additional site for addressing stigma. By framing activities as helping others or contributing to some common good, collective narratives allow professionals to push back against the negative perception of their work and to maintain a level of satisfaction with their job.

Our study also challenges the common notion that people in advertising are devoid of ethical standards. While advertising broadly may be guilty of promoting consumerism or propagating problematic stereotypes, understanding how advertising work is narrated at the day-to-day level is important for understanding how we can address those issues. We know that speaking to others’ values is helpful for persuasion, so understanding the ways advertising practitioners frame their work is important for figuring out how to design advertising policy.

No Comments