Research has demonstrated a dramatic rise of income inequality in the West. Today, across advanced capitalist countries, the top ten percent of households take home about a third of all income and own two-thirds of all wealth.

Despite what scholars, journalists and some politicians consider a worrying trend, there is no evidence that people have grown more concerned about inequality. In fact, citizens of more unequal societies are less concerned than those in egalitarian societies. How to make sense of this paradox?

Inequality paradox: citizens of more unequal societies are less concerned than those in egalitarian ones.

In new research I argue that unequal societies are marked by greater social distance between the rich and poor. Consequently, people on either side of the income divide underestimate the level of inequality characterizing their society and the role of structural advantages and disadvantages that got them to where they are.

Scholars have offered various explanations for people’s lack of concern about the growing income divide. First, people are often misinformed about the actual state of inequality in their society. Evidence suggests that citizens greatly underestimate just how unequal a society they live in.

Ordinary workers haven’t a clue how much money their CEO takes home. And CEOs largely have no idea how little their ground-level employees have to live on. In a recent survey, Americans put the income ratio at 30:1. In reality it’s closer to 350:1. What would be people’s ideal? An income ratio of 7:1. In other words, citizens may be unconcerned simply because they are unaware of the extent of inequality in their country.

A second line of scholarship suggests that living in an unequal society may actually make people more tolerant of inequality. People get used to inequality and develop successful coping mechanisms. We can think of the American Dream as doing just that. It sends a message of hope for those who haven’t yet reached their pinnacle. And, as a cultural narrative, it helps elites justify their privileges.

Neoliberal policies, rolled out throughout the West since the 1980s, have done a similar job. They reinforce the notion that success and setbacks in the free market are reflective of individuals’ efforts or lack thereof.

Inequality legitimates itself

I draw on these insights to develop an alternative theoretical framework. I argue that inequality creates the social conditions for its legitimation.

Unequal societies are marked by greater social distance. Rising inequality means that interactions across economic fault lines are becoming more seldom. Children grow up in poor or wealthy neighborhoods and attend different schools. They find friends and romantic partners in their own circles, and come to work in increasingly polarized labor markets.

Consequently, the rich and poor develop an understanding of society and their own place in it from a position of insulation. They underestimate the extent of inequality and the role of structural forces that help or hurt them.

Without direct experiences, news reporting and statistics about (growing) inequality are unlikely to challenge the meritocratic narrative. Nor will it lead people to develop empathy for the plight of unseen others living across the income divide.

Growing belief in meritocracy

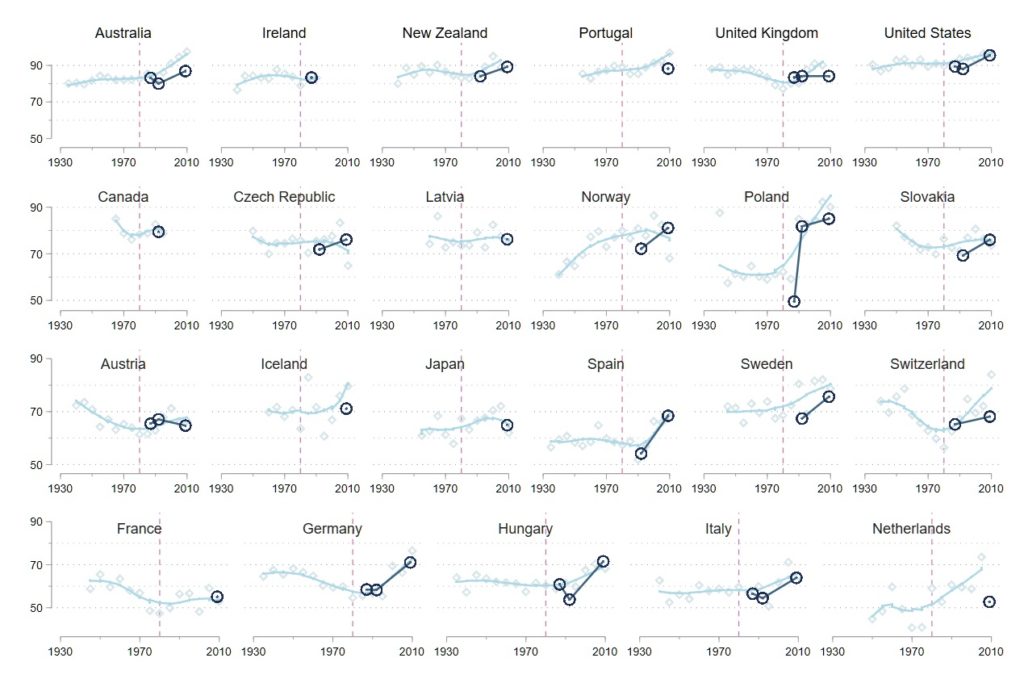

The figure below, from a recent study of mine, shows the trend in meritocratic beliefs across the West, between the 1980s and 2010s. Indicated, for each country and time point, is the extent to which citizens believe hard work determines who gets ahead in society.

Note: The vertical axis gives the percentage of citizens who believe that hard work determines who succeeds. The dark circles indicate popular beliefs for a given year. The light lines display popular beliefs for each 5-year cohort as indicated on the horizontal axis.

A first thing to note is how strongly citizens, across the board, think success depends on hard work. With the exception of communist Poland, a majority in each country and period believes theirs is a meritocracy society.

A second thing to note is that the percentage of people who believes their society is meritocratic has gone up in almost every country. Today, at least two-thirds of citizens in all countries—and as much as 95 percent of Americans—attribute success to meritocratic factors.

Rising inequality and belief in meritocracy

To understand the rise in meritocratic beliefs, I analyzed data from the International Social Survey Programme. The data cover 49,383 citizens in 23 countries, over a 25-year period.

In the first step, I looked at the Gini coefficient of income inequality and citizens’ beliefs about inequality. I find that citizens in more unequal societies have stronger beliefs in meritocracy and a weaker belief in structural inequalities, controlling for individual characteristics, country factors and secular trends over time.

Some of these patterns may however reflect static political and cultural differences between countries rather than changes over time. Does belief in meritocracy strengthen with rising inequality? Tracing changes in the Gini coefficient of income inequality over time, I find that the answer is yes: growing inequality has gone together with a stronger belief in meritocracy.

Explaining concerns about inequality

The second question is whether popular belief in meritocracy explains citizens’ concerns about inequality, or a lack thereof. To find out, I teased out the relationship between the two for working class, lower middle class and upper middle class citizens.

The analysis shows that concerns about inequality are much lower in societies where popular belief in meritocracy is strong. This is true especially for working class citizens.

Conversely, the level of concern is much higher in countries where people believe that inequality reflects structural forces. Working class citizens are much more concerned than the middle classes in societies where people don’t think of inequality as structural in nature. Where they do, all citizens share the working class’s concerns.

Stuck in a feedback loop

In sum, what explains citizens’ consent to inequality is their conviction that poverty and wealth are the outcomes of a fair meritocratic process. Citizens’ meritocracy beliefs are solidified by the fact that people are unable to develop an awareness of the structural processes shaping unequal life outcomes.

The reason for people’s inability to see what separates them from their fellow citizens is that the lives of the rich and poor are increasingly divided between separate institutions. People live in neighborhoods, go to schools, and pick romantic partners and friends that fit their education and income level.

As such, publics in unequal societies may find themselves stuck in a feedback loop. More inequality paradoxically leads them to experience less of it—and care less ab out it. Breaking that loop requires taking seriously people’s beliefs and lived experiences. And designing social policy to bring the two in closer alignment.

Until then, there is nothing surprising about the fact that people in highly unequal societies approach politics from the highly skewed vantage point of their own experiences.

Read more

Jonathan Mijs, “The Paradox of Inequality: Income Inequality and Belief in Meritocracy go Hand in Hand,” Socio-Economic Review 2019.

Jonathan Mijs,“Visualizing Belief in Meritocracy, 1930—2010,” Socius 2018.

Jonathan Mijs, “Inequality is a Problem of Inference: How People Solve the Social Puzzle of Unequal Outcomes,” Societies 2018.

Image: Jonathan Mijs

No Comments