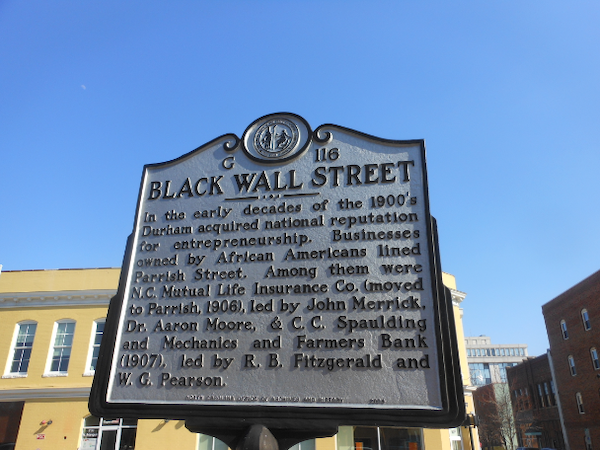

In downtown Durham, North Carolina, a sign commemorates Black Wall Street, a district that once hosted some of the most prominent businesses owned by African Americans in the city. The sign is located on a four-block stretch of Parrish Street, which is now populated by relatively mundane urban eateries, bars, luxury condos, and the Durham County Board of Elections. But between the late 1800s and 1960s, the area became known nationwide as a center of black enterprise and upward mobility.

The success of Black Wall Street was all the more striking because it occurred in the U.S. South during the era of Jim Crow. It was a time of white supremacist ideology, when state and local laws dictated the separation of blacks from whites in schools, public transportation, public amenities, and many private businesses. On Parrish Street and in the neighboring community of Hayti, black residents looked for paths toward economic advancement despite the hostile historical conditions.

They were not alone. For much of the last century, African Americans and a variety of immigrant groups lived in ethnic enclaves in the United States. The enclaves were marked by concentrated patterns of settlement and business enterprise in particular neighborhoods, often accompanied by the separation of enclave residents from other groups through barriers to interaction, including forced segregation, housing discrimination, restrictive covenants, and prejudice.

Ethnic enclaves have presented an enduring puzzle for sociologists who are interested in economic mobility: how did the residents in these enclaves fare economically relative to comparable individuals who lived outside of enclaves? On the one hand, enclaves could provide supportive social networks and a source of solidarity for minorities suffering from discrimination in a broader society. On the other hand, the enclaves also distanced residents from mainstream labor and consumer markets and could stigmatize the people who lived there.

In a recent study, we argue that the resolution to this puzzle hinges on the spatial scale of an enclave. Small clusters of co-ethnic neighbors provide a boost to upward mobility and entry into entrepreneurial activity, but large enclaves generate less advantageous outcomes.

We examine this hypothesis in the context of African-American economic mobility during the era of Jim Crow. Using Census data between 1880 and 1940, we track residential patterns, occupational outcomes, and entrepreneurship for representative samples of African Americans across the United States.

Our analysis includes the well-known founts of black enterprise at the time — cities such as Atlanta, Chicago, Durham, Memphis, and New Orleans — but also many smaller communities, as well as black households that were more isolated.

Our findings support the theory that occupational attainment is a function of enclave scale, with black residents in small enclaves benefitting from the presence of same-race neighbors and those in large enclaves suffering disadvantages in terms of occupational income and self-employment.

Historically, the enclave effects – both positive and negative — were weakest in 1880, at the beginning of the Jim Crow era, but much stronger in 1910 and 1940, when Jim Crow had become institutionalized. Looking at geographic variation, the pattern was especially pronounced in states with Jim Crow laws that imposed racial segregation on businesses and neighborhood amenities.

For modern urban planners, the results highlight the importance of scale in designing neighborhoods, especially in areas that are racially or economically homogenous.

The case of Durham is instructive. With over 3,000 African-American residents by the 1950s, the Hayti neighborhood was too large to share in the success of Black Wall Street and too segregated to benefit from economic growth in Durham more generally.

Under the guise of “urban renewal”, the Durham Freeway was built through Hayti in the 1960s, forcing hundreds of businesses and thousands of residents to relocate. The construction separated Hayti from Parrish Street and created years of disruption for the black community. Sadly, today little remains of the original Black Wall Street except for a sign.

Read More

Martin Ruef and Angelina Grigoryeva, “Jim Crow, Ethnic Enclaves, and Status Attainment: Occupational Mobility among U.S. Blacks, 1880-1940,” American Journal of Sociology 2018.

Image: Alexisrael via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

No Comments