At least one good thing has come out of Amazon warehouses. The horror stories about the company’s working conditions—including sonic wristbands that follow employees’ every move—have increased public concern about the potential dangers of workplace surveillance. Beyond Amazon, workers across a range of industries are already being tracked and monitored.

In a recent article, I focus on the digital surveillance of fast fashion retail workers. Fast fashion chains such as Zara and H&M are known for selling a tremendous amount of trendy, cheap clothing. Less well known about these companies is the extent to which they too rely on a vast amount of data—tracking customers and workers alike—to keep their stores running.

Between 2015 and 2018, I immersed myself in this industry. I worked as a sales associate at two major fast fashion retailers in New York City, interviewed twenty other retail workers, volunteered with a retail workers’ center, and attended corporate retail conferences where the latest technologies were on display.

I found new surveillance technologies almost exclusively worked in employers’ interest, making new demands of precarious workers and reproducing broader social inequalities.

Surveillance at Work

One of the most well-known forms of data-driven worker management is automated scheduling.

As journalists and organizers have found, because of automated flexible scheduling, retail workers often have no idea how many hours they’ll be asked to work from week to week, and thus lack any economic security. Employees are sometimes asked to work “clopening” shifts, closing one night and opening the next. Others are scheduled “on-call” or more simply asked to go home before the end of their shift and called in on their days off.

Companies like Kronos, which manufactures automated scheduling software, are huge drivers in the spread of flexible scheduling. Kronos’ software uses algorithms that analyze a vast amount of data—including current and former customer traffic, employee performance, and even the weather—to determine how many, or more importantly, how few, workers are needed at any given moment.

I found that Kronos’ impact isn’t limited to scheduling. By creating a more flexible, part-time, and on-call workforce, automated schedulers create the need for even more digital surveillance to simply keep track of employees.

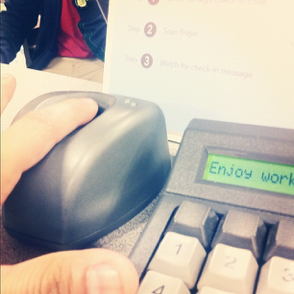

For example, along with its automated schedulers, Kronos also promotes its biometric timeclocks. With these devices, workers clock in and out by scanning their fingerprints. Kronos advertises these clocks as built for “today’s modern workforce,” having “rock solid” reliability to determine a worker’s “true identity.”

Both retail stores I worked at used biometric timeclocks. While they might have cut down on “time stealing” (in which a worker attempts to get paid for time not worked) or “buddy punching” (in which employees clock in for someone else who is running late, or clock out for someone else who leaves early), they also led to various forms of wage theft.

These “rock solid” clocks regularly broke down at both locations I worked. One of my interviewees shared:

It was annoying, sometimes [the fingerprint scanner] didn’t work. You’d have to let a manager know, and then they’d put in the time for you… And that was really annoying because, like, everything’s really hectic, everything’s really busy… [This happened] When I first started working there, I didn’t get paid for like weeks of work.

In addition to biometric timeclocks creating hassles at the beginning and end of each shift, retailers increasingly track workers throughout the store. In my fieldwork this occurred most clearly at the cash register. By requiring employees to log in with their personal ID, point-of-sale software could aggregate cashier performance and combine it with CCTV video footage, allowing companies to identify and discipline “high risk stores” and “high risk cashiers.”

During my new-hire orientation, the employee training us said there was a simple button we could use as often as we wanted to void a transaction if we made an error. The manager on duty spun to her and snapped, “You know we track that, right?” The employee’s eyes grew wide in distress.

Yet another employee I interviewed told me he once put five dollars—half an hour’s wages—from his own pocket into the register when his drawer came up short; being reprimanded for previous mistakes had been “terrifying.”

While supposedly increasing efficiency for employers, tracking technologies frame workers as potential criminals and increase stress. Amid life-jumbling automated schedulers, unreliable biometric scanners, and anxiety-provoking point-of-sale monitoring, low-wage retail workers must resist becoming overwhelmed so they can keep clothes and customers moving. I call this requirement of working under increasingly pervasive digital monitoring the “emotional labor of surveillance.”

Worker Surveillance and Inequality

A growing number of scholars and activists focus on how surveillance disproportionately impacts already marginalized communities, and retail is no exception.

Fast fashion is one of the most precarious sectors of clothing retail labor; most of my coworkers and interviewees were women, people of color, and/or LGBTQ. When thinking about how surveillance effects low-wage workers, we must also think about how these same populations are already being tracked across society.

As I have written elsewhere, many of the same companies that create worker monitoring technologies also produce tools for law enforcement and the military. These connections should raise concerns about how employers store worker data (such as fingerprints), who might have access to those data, and to what ends.

Read more

Madison Van Oort, “The Emotional Labor of Surveillance: Digital Control in Fast Fashion Retail” in Critical Sociology 2019.

Image: Rondo Estrello via Wikimedia Commons (cc-by-sa-2.0)

2 Comments

[…] too. Kaoosji noted the rise in employers tracking the keystrokes of at-home workers and other retailers emulating Amazon’s surveillance regime. UPS drivers, for instance, ferry packages across the […]

[…] too. Kaoosji noted the rise in employers tracking the keystrokes of at-home workers and other retailers emulating Amazon’s surveillance regime. UPS drivers, for instance, ferry packages across the […]