During the height of the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, workers producing military supplies were at the heart of a strike wave in the United States, calling for a more equitable distribution of war-profits in the form of higher wages and better benefits. Although little attention has been paid to them, such strikes by manufacturing workers in war-industries have caused nearly 2.2 million working days lost in recent decades.

This is not a new phenomenon: During the large wars of the twentieth century, industrial workers in the United States regularly engaged in strikes that raised their wages and ushered in new institutions designed to protect workers’ rights.

These recent strikes—alongside this historical relationship—raise an important question: How have U.S. wars affected workers in the twenty-first century? In a recent article, I explore this question by reviewing strikes by manufacturing workers in war-industries.

This research reveals that workers’ struggles have changed over the course of the twenty-first century. These changes were caused, in large part, by changes in military actions and strategy—most notably, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Obama “pivot” to East Asia, and escalating “great power” rivalry. In short, changes in warfare affect the power of workers who supply materials for war.

Importantly, studying the relationship between war and workers not only helps us understand the domestic consequences of present and future military actions, but also how workers can improve their conditions without relying on the waging of ‘endless’ wars.

Why does war affect workers?

Wars often lead to increases in production, tighter labor markets, and higher wages. The large twentieth century wars contributed to declining inequality, the growth of the welfare state, and the advance of civil rights in the United States.

For these reasons, social scientists have long understood that wars can have an empowering effect on workers.

This empowerment is because the government relies on workers during wartime to produce supplies and to serve as soldiers. This reliance translates into what is called bargaining power, or the leverage that workers have from their ability to disrupt activities like production and war. Workers can use their bargaining power, often through strikes, to achieve demands like better wages, benefits, rights, and protections.

For example, during World War II, workers went on strike in key war industries, leveraging their bargaining power to create a new norm of relations between governments, businesses, and workers. For a time, this arrangement codified their rights and allowed wages and working conditions to steadily improve.

But for many reasons, this arrangement was short-lived. By the 1980s, “deindustrialization” and “outsourcing” caused mass layoffs in industrial manufacturing, precipitating a crisis for workers in the United States. Workers faced shrinking wages, growing job insecurity, and falling union densities.

The strength that workers had in the middle of the twentieth century was severely eroded by the turn of the twenty-first. So what does this mean for the relationship between war and workers’ power today?

Strikes in war industries

I found that, like in the mid-twentieth century, the start of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan increased the bargaining power of workers producing war-materials. Between 2003 and 2009, corresponding with the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, these workers engaged in a series of offensive strikes—or strikes demanding increases to wages or benefits. But after this wave, the strikes became defensive in character, meaning they were fought against reductions in wages, benefits, or employment levels.

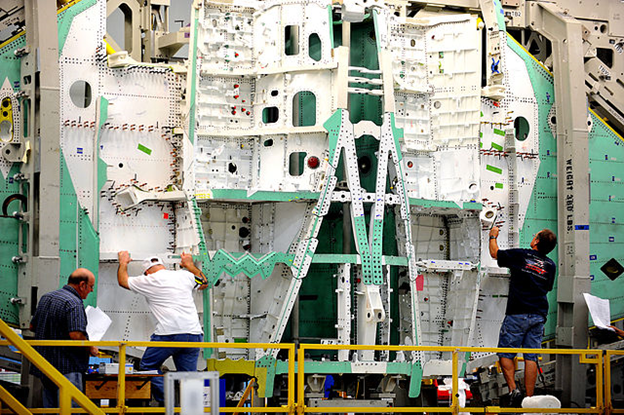

One worker striking at a Lockheed Martin F-16 plant in 2003 noted: “…this year we absolutely are in a different position [than before the war]—there are record profits at Lockheed Martin. We are asking for a fair contract.”

By leveraging the government’s reliance on the supply of F-16s to the new war in Iraq, workers were able to win better wages and benefits. This happened many times across the country during the mid-2000s for workers producing everything from jets and helicopters to missiles and rockets. As one striking worker acknowledged in 2006: “They [the military] do depend on our aircraft, but it’s not our fault that we’re out here.”

As the wars dragged on, strikes continued—but, unlike the wave in the mid-2000s, these struggles became defensive in nature.

After 2009, there was a shift. Military contractors began cutting pensions, announcing layoffs, and reducing benefits. Workers were pushed into a defensive posture, and they had to fight for their livelihoods.

In part, this was because “deindustrialization” and “outsourcing” since the 1980s made it easier to move production of war-materials to cheaper labor markets. Recently, the U.S. government relaxed standards for buying foreign-made military goods.

But just as important was a change in the type of war-materials these workers produced.

In the first years of the wars, workers were producing urgently needed military goods—like the F-16 fighter jet. This meant that the government was relying on workers to provide an uninterrupted supply. This empowered workers and allowed them to win when they went on strike.

But in more recent years, workers at these same plants are producing different goods. For example, instead of the F-16, workers at the Lockheed Martin plant are now producing the more advanced F-35s.

Why does that matter?

These new weapons systems are currently not being used in wars. Workers are building new models designed for war with “great powers” like China or Russia—not with insurgents in Iraq or Afghanistan. This means that the military does not urgently need their products—and that the government is not relying on workers to quickly supply them.

By not supplying war-materials that the government urgently needs, workers have seen a severe reduction in their bargaining power over the past decade.

War changes—and workers’ power erodes

The growth in production of new (and less useful) weapons systems was related to a broad shift in U.S. grand military strategy. Around 2009, Obama’s “Pacific Century” project meant that the conflicts in the Middle East took a backseat to rivalry with China.

Such changes in geopolitical strategy affect workers in the United States. Workers continued to build war-materials, but now they were largely in preparation for an uncertain future conflict. This reduced the government’s reliance on them and eroded their bargaining power—resulting in layoffs, wage cuts, and reductions in benefits.

If anticipated “great power” conflict never erupts, then we will likely not see a renewed empowerment of these workers.

However, at times, Trump has seemed eager to wage war. It is likely that any significant expansion of warfare would put pressure on workers to produce war-materials and empower them—at least temporarily.

But the workers’ empowerment in the mid-2000s was much narrower and shorter-lived than in earlier wars, when improvements were won for large segments of the working class. Given the narrow and uncertain empowerment that comes from current wars, the present moment may offer workers the opportunity to look elsewhere for more stable empowerment. But more than that, finding new sources of power could begin the important process of disentangling the interests of workers from the death and destruction of U.S. wars.

Read more

Corey R. Payne. “War and workers’ power in the United States: Labor struggles in war-provisioning industries, 1993-2016” Journal of Labor and Society 2020.

Image: Cherie Cullen via Wikimedia Commons

No Comments