Why are women less interested than men in applying for startup jobs? In a new article published in the Academy of Management Journal, we uncover an essential piece to this puzzle: Women are less interested in applying for startups when fewer women are already employed in these startups. Confused already? Let’s take a few steps back and try to explain this catch-22 situation.

Diversity debt

Women are underrepresented among entrepreneurs and their investors, but also among “joiners” – the distinct group of people who are attracted to employment in startups but have little desire to become founders.

When startups scale their workforce, they often accrue “diversity debt”– an initially skewed gender composition that demands costly and often unsuccessful attempts to remedy gender disparities as the organization grows.

Analyzing more than half a million application decisions on a job-matching mobile app for startups (think Tinder for startup jobs), our first study shows that women’s underrepresentation in startups deters other women, but not men, from entering the candidate pool. This effect was most substantial for startups that signal diversity debt – the startups that show no or only a token representation of women (on the app we studied, every employer was required to report their current gender composition as a standard on each job post, next to other company information such as industry affiliation, company age, etc.).

For women to be hired, they must be well-represented in the candidate pool. Because of this, a gender gap in applications implies the beginning of a vicious cycle. When startups employ far fewer women than men, this deters other women from applying. Because there are fewer women applicants, startups then hire more men, reinforcing the existing gender composition and further deterring other women from applying, and so on.

Lack of fit and identity threat concerns

When joiners ponder whether to apply to a particular startup, why are women, but not men, sensitive to information about the existing gender composition at the company?

Based on seminal research on the Lack of Fit Model, we argue that women, who are traditionally underrepresented in startups, pay special attention to information about the gender of the people they are expected to work with. When no specific information is available, women determine their fit based on broader gender stereotypes – preconceptions about the gender-typing of a work environment as masculine or feminine. But as new information about company-specific gender composition becomes available, preconceptions are revised, and with them also fit or lack of fit perceptions.

Unlike women, men, as the dominant majority in this context, are less sensitive to gender-related information simply because it is less likely to influence their anticipated fit with the company upon applying.

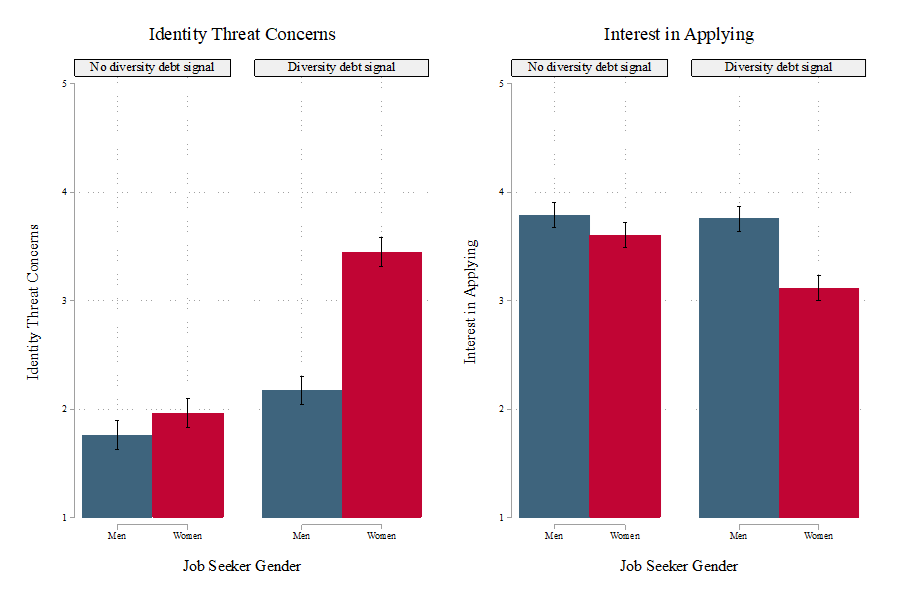

In our second study, using a preregistered experiment, we dive deeper to examine the psychological mechanism linking diversity debt signals and joiners’ interest in applying. Recall that diversity debt signals indicate a severe underrepresentation of women. Consistent with classic writing about Tokenism – the observation that women suffer more adverse consequences in skewed groups (up to 15 percent women) than in tilted (15 to 35 percent women) or balanced groups (35 to 50 percent women) in terms of gender balance – our experiment assigned joiners to view one of two startup employer profiles, which were identical in all but the organizational gender composition they showed. One of the profiles showed 40% women, the other just 5% – that is, it sent a powerful signal of diversity debt.

We hypothesized that such an extreme gender imbalance would likely affect women’s expectation of becoming a token themselves and consequently prompt a set of Identity Threat Concerns – worries about the prospect of being singled out, disrespected, stereotyped, marginalized, or mistreated.

The results were crystal clear (see Figure 1 below). Signaling diversity debt triggered identity threat concerns for women but not for men. In turn, identity threat concerns were associated with gender sorting into the candidate pool. The more concerned women were, the less likely they were to express interest in applying.

This effect was also illustrated by answers the participants provided when asked to explain their application decisions in this study: Women often mentioned the lack of diversity as a major drawback and reason not to apply. For example, they answered: “I immediately get “tech bro” vibes from this place, and it is somewhere I am not interested in,” “I would be a bit intimated,” or “As a woman, I feel like I wouldn’t be taken seriously.”

So what?

That women are sorely underrepresented in and around startups is not just an operational problem for founders or a theoretical puzzle for scholars, but also a societally relevant problem with implications for gender equity and inclusion overall.

Consistent with the view that supply-side (job seeker preferences) and demand-side (employer decisions) drivers of gender inequality in organizations interact in complex ways, we show that in evaluating potential employers, women incorporate an anticipation of what this work setting would be like, given available information about organizational gender composition.

Specifically, we found that startups signaling diversity debt push women away by setting off concerns that one’s gender identity will be devalued or threatened. This provides a potentially parsimonious explanation for the persistence of gender disparities in this context. Regardless of its origin, be it in the imprinting of founding team gender composition, discriminatory hiring, or idiosyncratic job seeker choices, exposure to diversity debt signals is seemingly sufficient to trigger concerns in women and thus maintain a gender gap in application interest for startups.

The most straightforward recommendation based on our findings is that startups should pay close attention to organizational gender composition from the get-go, especially with the first few hires. Rather than spending ever-increasing resources on diversity initiatives that rarely work at scale, young startups that can successfully demonstrate their ability to hire and retain women early on may potentially outcompete their peers in the “war for talent.” Our results further reveal that such efforts to recruit more women would not necessarily risk alienating men since men were largely inattentive to gender composition signals.

With the recognition that most startups operating today might already have some level of diversity debt, our conclusions might seem pessimistic and our recommendations to avoid diversity debt unrealistic. But not all is lost. Diversity debt doesn’t have to mean that startups are doomed to forever scare women away from joining. It just means they must find alternative ways to make women feel safe.

For example, once startups acknowledge their active role in shaping women’s interests, they can proactively lead initiatives to become more attractive to this important subgroup of the joiner population. Indeed, rather than ignoring the situation or habitually blaming the “pipeline problem” – citing grand societal forces or women’s innate preferences as the main reasons for them dropping out of the hiring funnel – startups should take responsibility for their part in affecting who enters the candidate pool.

At least before they scale, startups represent a unique organizational context where self-reinforcing processes can still turn from vicious to virtuous.

Read more

Yuval Engel, Trey Lewis, Melissa S. Cardon, and Tanja Hentschel. “Signaling Diversity Debt: Startup Gender Composition and the Gender Gap in Joiners’ Interest” in Academy of Management Journal 2022.

2 Comments

You studied workforce competition. Did you also collect data on the composition of the founding team? I would think that the gender composition of the founding team would send an even stronger signal to potential applicants about the possible “bro culture” that might encounter at a start up.

Great study design, by the way.

Hi Howard, thank you! Yes, we did include data about the founding team composition in our analyses! However, the gender composition of the founding team, unlike organizational gender composition, was not part of the information available to job seekers on the ads (so in our Study 1, for example, job seekers would have needed to look for this information independently in order for it to influence their decisions). In addition, while it might indeed send a relevant signal, the gender composition of founding teams is perhaps a noisier signal of “bro-culture” (or any such threat-inducing cues for women) than organizational gender composition (we cite in the paper some mixed evidence in prior work for founders’ gender and differential attraction of job seekers by gender). Think about it this way – a men-only founding team might still build a diverse and inclusive environment with equitable treatment of men and women alike. In other words, in growing the startup they can still make decisions that deviate from the path “determined” for them by their initial founding team composition. Yes, that’s not the most likely outcome, but it is certainly possible and some job seekers might give such employers the benefit of the doubt. In contrast, a gender skewed workforce composition in which women are severely underrepresented is a step further in that it represents a series of already-made decisions by which men were recruited, selected, and hired at a much higher rate than women. The signal such consistent past behavior is communicating to job seekers is most probably much more powerful than any signal the founding team composition might imply. At least that’s how I come to think about it… I hope it answers your question. Thank you again for engaging with our work!