After President Trump withdrew from the Paris Climate Accords, several hundred mayors signed national and global treaties announcing their commitments to “step up and do more,” as a senior official of the City of New York told me in a poorly lit room in 2017. Cities were rushing to the forefront of adopting practices and policies to address contemporary social and environmental problems, such as climate change.

What the general enthusiasm masked is significant variation in the extent and speed at which cities adopt these innovations. The We’re Still in Campaign, supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies, actively pursued mayors of all colors to join the movement. But even with mayoral and philanthropic support, many cities have refrained from taking drastic action to protect the environment.

This variation reflects a general problem, frequently observed when it comes to local initiatives about infrastructure for electric vehicles, gender-neutral bathrooms, reigning in police violence, or even the desegregation of schools. Some cities are quick to transition to new ways of doing things, while others are slow to respond or do not adopt such social innovations. A recent study of the energy transition in US cities shines a new light on the origins of such disparities.

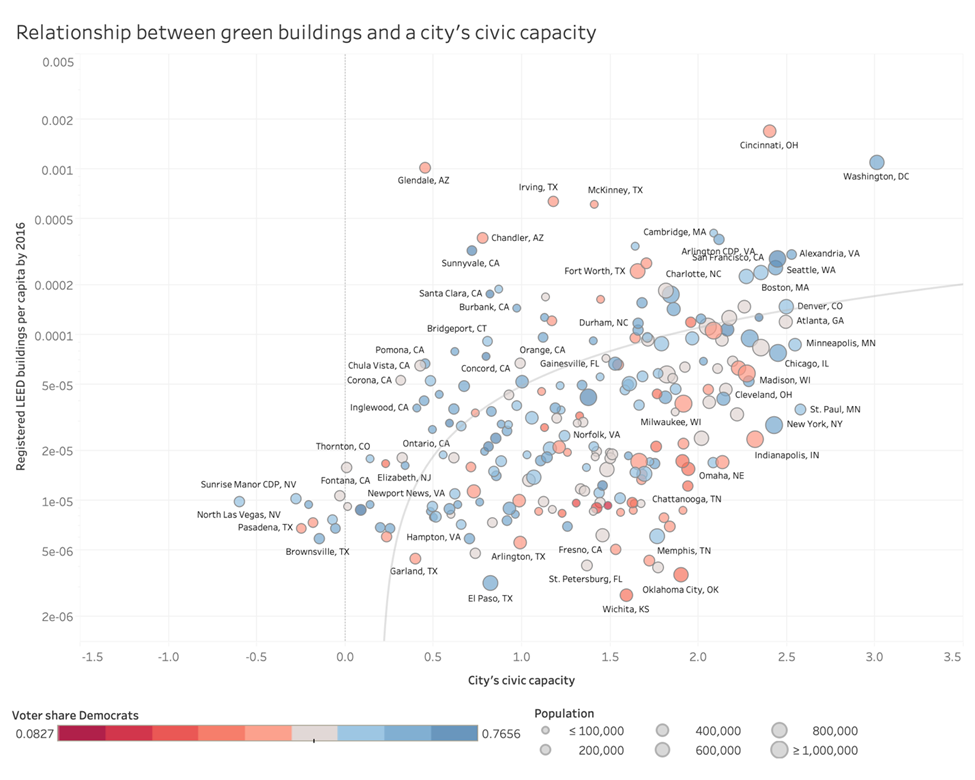

My study of the geographic dispersion of green buildings certified with the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system, published in the American Journal of Sociology, suggests that the organizational communities within cities play a significant role in adopting urban innovations. Cities with a robust civic capacity, where values-oriented organizations actively address social problems, are more likely to adopt new practices quickly and extensively. Civic capacity matters not only through structural channels, as a sign of ample resources and community social capital, but also through organizational channels. Values-oriented organizations are often early adopters of new practices, such as green construction, solar panels, electric vehicles, or equitable hiring practices. By creating proofs of concepts, these early adopters can serve as catalysts of municipal policies and widespread adoption.

To illustrate the findings of the paper, consider the city of Chicago. Chicago has a robust network of nonprofit organizations that are actively involved in addressing social and environmental issues. For example, the local chapter of the US Green Building Council, the Illinois Green Alliance, has been working to promote the adoption of green construction practices and policies in the city. Chicago has seen constant growth in the adoption of green construction, with several new net-zero buildings dotting its skyline.

The city of Cleveland provides an illuminating contrast. Cleveland has a weaker network of values-oriented organizations and has seen slower adoption of green construction practices. Despite early efforts to advance sustainable development by advocacy organizations like the Cleveland Green Building Coalition (a precursor of the local chapter of the US Green Building Council for North Ohio), green construction did not take off in the early years. Today, Cleveland features roughly half as many green buildings per inhabitant as Chicago.

This example shows how even modest differences in the presence of values-oriented organizations can influence the adoption of urban innovations. The figure shows the position of cities over 100,000 inhabitants with respect to their civic capacity (the presence of nonprofits adjusted for the demographics and politics of the city) and their green building count after some 15 years of diffusion. Places with more robust civic capacity are more likely to see quicker and more extensive adoption of new practices aimed at social innovation. These findings hold even net of other features such as wealth, city size, and geographic location, the study shows.

The paper also finds that municipalities are often inspired by the early actions of civil society organizations when it comes to adopting new practices and policies. These organizations can serve as proofs of concept, showing that new practices can be successful and effective. As a result, city governments are more likely to pass legislation that legitimizes the actions of these organizations and shapes the actions of other organizations in the city.

One example of this dynamic is the city of Cincinnati, which saw early successes such as the LEED certifications of University of Cincinnati’s Student Life Center, a building at the Cincinnati Zoo, and the corporate headquarters of renewable energy supplier Melink. Since 2006, Cincinnati has incentivized green construction by offering property tax exemptions on parts of the assessed value of LEED-certified buildings. This policy significantly affected the adoption of green construction in the city. Today, Cincinnati has more LEED-certified buildings per capita than any other city in the United States.

Overall, the findings suggest that the organizational communities within cities play a crucial role in the adoption of urban innovations. Civic capacity helps cities and their leaders come up with new takes on social problems and adopt ostensible solutions for them. This has important implications for understanding the role of nonprofit organizations in developing reactions to climate change and promoting urban innovation more generally.

Understanding how civil society organizations initiate novel practices can help explain a range of sociological problems. In economic development, the presence of values-oriented organizations may be a critical factor in the success of initiatives such as opportunity zones, which aim to stimulate economic growth in disadvantaged areas. In the realm of environmental policy, the involvement of these organizations could be crucial for the success of initiatives such as bicycle and EV programs, as well as bans on single-use plastics such as bags and straws. Proofs of concept established by early adopters can make the difference between the success or failure of such initiatives.

In addition to its implications for the study of novel practices in cities, the paper also shines a light on how catalysts get new practices going before they take off—returning to organizational sociologists’ seminal insights that the first step towards diffusion looks different than later dynamics. The interplay between distributed adoption among decentral members (like organizations located in a city or employees of a company) and administrative adoption among central authorities (like city hall or bosses) can explain all sorts of diffusion processes in organizations and society more broadly.

Future work may shine a light on the collective impact of other individual actions. Certain scope conditions affect the processes identified in the paper, such as legitimacy in the broader social context and the fact that individuals (or individual organizations) can adopt the practice as well as a central authority (i.e., a company’s management or a country’s government). Examples of behaviors that meet these conditions include efforts to increase workplace diversity, support worker rights, and improve openness and transparency.

Read more

Christof Brandtner. “Green American City: Civic capacity and the distributed adoption of urban innovations” in American Journal of Sociology 2023.

For a free, pre‐publication version of the article, see here.

Image: Conservation Design Forum via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

No Comments