The joint growth of income segregation and inequality across Western nations calls attention to the changing conditions of life on each end of the growing divide. Alongside the material consequences of this process, there is an important cognitive aspect: as social worlds become increasingly divided by socioeconomic fault lines, how do we learn about the lives of others?

Sociologists are beginning to address this question by describing how people make sense of inequality. Understanding how we perceive and explain inequality is important because our beliefs, in turn, are predictive of a host of political attitudes on topics ranging from healthcare to redistribution and the welfare state.

My article in Research in Stratification and Social Mobility sets out to learn how young Americans growing up in a country defined by inequality and segregation learn about their society. I investigate this question in the context of college. School, more than any other institution today, provides the context for children’s cognitive, social and moral development, for its presence in children’s lives across the Western world is sustained, durable, and compulsory.

Institutional inference

I theorize that (young) people learn important lessons about inequality in their society from the economic and racial homogeneity or heterogeneity of their neighborhood, school, and workplace context. I conceive of a process of institutional inference whereby people draw from experience and available information to develop an understanding of inequality. Socializing institutions like college shape this process by providing a durable context to young adults’ interactions with others in this crucial developmental stage.

Through their recruitment and admission practices, colleges determine the exclusivity and heterogeneity of the context in which students learn important lessons about social and racial inequality in the US. In doing so, they shape the development of students’ inequality beliefs by exposing them to a certain type and range of information, but not to their counterfactuals. Through their institution, a person may gain access to experiential evidence and particular narratives about the meritocratic and structural causes of inequality that lie outside their own biography.

Crucially, racial and socioeconomic diversity provides students with information indicative of the structural sources of inequality in their society, i.e., how race and family background may help or hinder social mobility. A college environment with minimal diversity keeps this kind of information from students and does not provide counterevidence to the dominant meritocratic view of society.

Belief change in college

I empirically test my theoretical framework by tracing the inequality beliefs of ten cohorts of US college students between 1998 and 2010, totaling 141,597 college students across 436 institutions. Data come from the Cooperative Institutional Research Program which partners with colleges to survey students about their attitudes and experiences in college. It is a national panel of students across residential four-year colleges in the US, which include elite research universities (e.g., Dartmouth College), highly selective public schools (e.g., University of Michigan—Ann Arbor), and non-selective private and public institutions.

To describe change in students’ beliefs, I combine The College Freshman Survey, a survey taken before students start college, typically at freshman orientation, and the College Senior Survey, which is an exit survey taken by those same students in the spring semester of senior year, four years later. Belief change is identified by estimating two-way student fixed effects regression models.

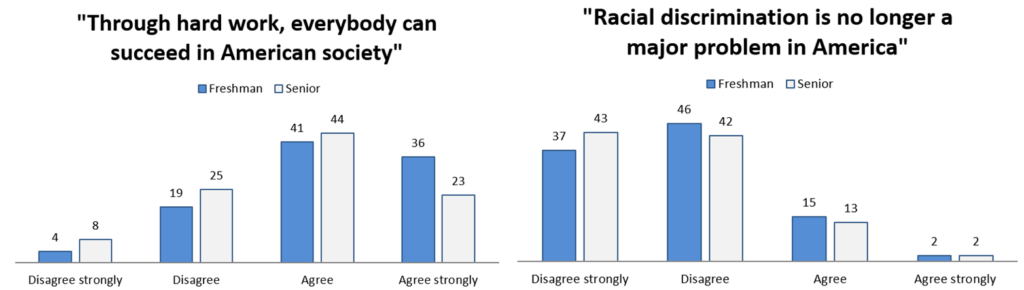

So, do students believe America is a meritocracy, and that racial discrimination is a thing of the past?

I find that most freshmen believe in meritocracy, but they also acknowledge racial inequalities.

By senior year about half of students have held on to their beliefs, whereas some 20% have grown more convinced that theirs is a meritocratic society, and 30% now see their society as structurally unequal, meaning that inequalities reflect an unfair playing field.

To study why students change their beliefs in one or the other direction, I consider three features of the college context, being: (1) the ethnic and racial background of their roommates, and the degree of (2) racial and (3) socioeconomic diversity in the student body of their college.

My main focus is on students’ shared living arrangements with a roommate which, I argue, provide a unique lens into the social and material conditions of another person’s life. However, I acknowledge that college campuses offer a range of other opportunities for meaningful interactions, including classes, clubs, and sports. Hence, I investigate the impact of having a different-race roommate in more and less diverse campus contexts.

Roommate effects

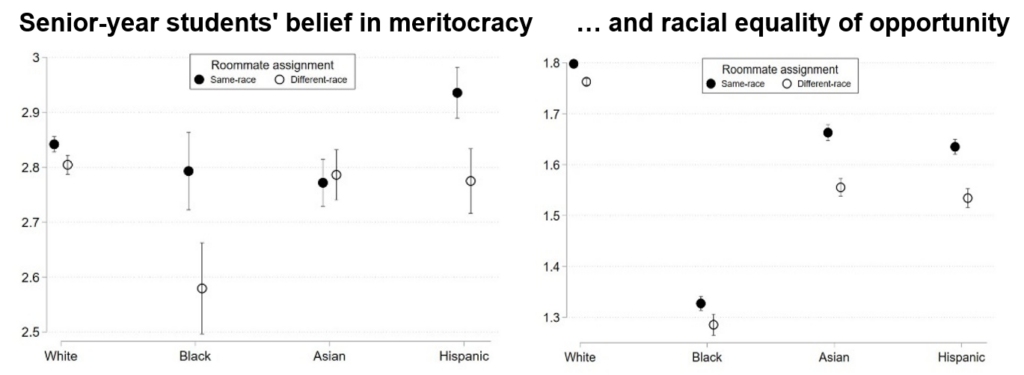

My research reveals that having a roommate from a different racial or ethnic group is associated with students developing a less meritocratic understanding of America. Black and Hispanic students, especially, lose faith in meritocracy, and Asian students come to see more racial inequality.

The average effect of roommate pairing on inequality beliefs that I find are about an eight of a standard-deviation of the within-student variation in beliefs; similar in magnitude to the effects of college completion on a person’s support for civil liberties and gender equality, as estimated with sibling fixed effects or age-period-cohort models, as reported in past research. This suggests that rooming with a person of a different race may have as much impact on a person’s beliefs about inequality in America as the (liberalizing) effect of going to college as such.

Ironically, white students are less affected by their roommate than non-white students. This asymmetric impact of experiences with diversity may be illustrative of people’s higher attentiveness to personal disadvantages than those facing others. To the students involved, a particular experience may reveal both privilege and disadvantage, but another person’s privilege is easier to recognize than one’s own – especially, it would seem, for white students. Let’s also acknowledge that what may constitute an eye-opening experience for some, can be a draining and psychologically costly confrontation for another.

Another finding speaks to the broader college context: The effect of having a roommate from a different race or ethnicity, I find, is strongest at places that lack socioeconomic and racial diversity, such as colleges with a majority white student body or schools where the lion’s share of students have college-educated parents. That is, diversity experiences matter most where they are least likely to happen.

College reinforces inequality

My findings suggest that the college context deeply shapes students’ view of inequality. Historically, colleges have had the mission to educate young citizens (“tomorrow’s leaders”) about their country’s past and present, the democratic process, and their part in it. They have the potential, more generally, to broaden students’ perspectives and increase intergroup understanding. Currently, however, a majority of students receives only limited exposure to socioeconomic and racial heterogeneity, both directly and in the campus environment.

For many students, then, increasing diversity in the overall population is met with social isolation in the microcosm of higher education. With little exposure to diversity, adolescents grow up to develop a naïve understanding of American meritocracy in a country that is increasingly divided along racial and economic lines. For these students, the college experience undermines rather than serves the civic and integrative role of higher education.

College, then, reinforces inequality in two ways: (1) credentials increase the economic gap between graduates and the 70% of Americans without a degree, and (2) when colleges lack diversity, tomorrow’s educational elite learns to legitimize the growing gap as meritocratically deserved.

More exposure to heterogeneity creates conditions under which students can develop an awareness of the structural processes shaping inequality. Be it through purposeful roommate pairing, inclusive admission policies, or affirmative recruitment efforts, a college environment that better reflects our diverse population would impact the perspective of 20+ million students currently in college and, with it, public opinion and US politics.

Read more

Jonathan J.B. Mijs. “Learning about inequality in unequal America: How heterogeneity in college shapes students’ belief in meritocracy and racial discrimination.” Research in Stratification and Social Mobility 2023.

Jonathan J.B. Mijs and Elizabeth Roe. “Is America Coming Apart? Socioeconomic Segregation in Neighborhoods, Schools, Workplaces, and Social Networks, 1970 – 2020.” Sociology Compass 2021.

Jonathan J.B. Mijs. “Inequality is a problem of inference: How people solve the social puzzle of unequal outcomes.” Societies 2018.

image: Jonathan Mijs.

No Comments