Organizing is hard. It is hard to organize workers to improve their working conditions and seek redress for workplace abuse. And it is especially hard to organize low-wage workers who inhabit the deregulated, fissured workplaces of the post-Fordist labor market.

The challenges of organizing low-wage workers are as much structural and institutional as they are tactical. Formal legal protections are only as good as the ability of workers to engage in individual and collective claims-making to pull the “fire alarm” of a wage theft claim, prompt an Occupational Safety and Health Administration(OSHA) investigation, or initiate a sexual harassment complaint, for example. Worker advocates have stepped in to help bridge that gap. Their work is more critical now than ever as union membership has plummeted and is nearly nonexistent in many of the jobs and industries that many vulnerable workers occupy.

To this end, worker centers and other alt-labor groups have developed creative mobilization strategies to support worker claims and build worker power in the low-wage labor market. Since 2008, we have engaged in research with low-wage workers who participated in the individual and collective claims making processes of two worker centers, one in Chicago and the other in the San Francisco Bay area, both serving low-wage, mainly immigrant worker constituency.

The low-wage workers whose claims making processes we documented through participant observation and interviews described how the structural challenges inherent in current regulatory regimes manifested themselves in their own experiences. We learned how they navigated the complicated and often brutally conflictual processes of claims-making. These workers described how they suffered when their rights are violated on the job, what it was like coming forward to make a claim, and what kind of resolution they were often able to reach (or not). While our aim is not to clinically diagnose “trauma,” the workers we spoke to clearly, unambiguously, and poignantly expressed the emotional strain, psychological stress, and social burdens of the claims making process.

That said, the bottom-up claims making process can also be transformative for participants. Many workers found those initial wins empowering, and worker centers rely on those victories to motivate and sustain their organizing efforts. Yet, the finite resources required by a claims-driven system that relies on individual and collective worker agency makes this approach an unsustainable way to reregulate the labor market. Our findings highlight the necessity of worker centers and other community organizations to help hold employers accountable. We also, however, point to the critical need for additional proactive strategic enforcement efforts on the part of regulators.

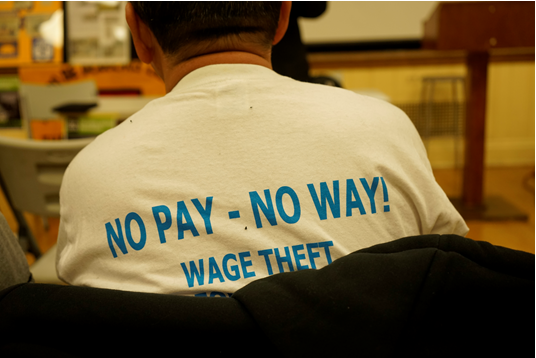

These findings are informed by the wide array of abuses workers experience. For example, the most common experience of workplace abuse for workers was “wage theft,” nonpayment or underpayment of wages owed, which created a cascade of emotional and financial stress as workers scrambled to make ends meet. But beyond the economic fallout of not being paid for their time, workers spoke of personal humiliation, a loss of dignity, and many times blamed themselves for having their workplace rights violated. Some even compared this ubiquitous trend of stealing workers’ wages to intimate partner abuse and talked about grieving in the aftermath.

While worker centers frequently provided a safe and supportive space to mitigate these psychosocial challenges, the adversarial and frustrating bureaucratic claims-making process triggered recurring stressors. Not only did workers have to navigate agency staff, but also relationships with co-workers, while also confronting recalcitrant bosses, and risking being blacklisted.

Worker center staff became critical for supporting workers as they confronted employers, decided whether to initiate a formal claim, and struggled to see these processes to the end (sometimes spanning years). Many claimants spoke of evocative experiences of empowerment, such as community driven campaigns that built a movement of supporters to rally alongside aggrieved workers to rupture the illusion of unilateral employer power. These moments mitigated the stress of claims-making and helped connect workers to a broader struggle. For example, one retail store employee, after participating in a direct action with the worker center in Chicago to confront his boss for three years of wage theft movingly exclaimed “Me siento desahogado” (I feel like a drowning man who has come up for air).

These moments can produce tangible redress for low-wage workers and a collective victory in the unending task of reregulating the labor market from below. But workers commonly describe these movements of success as ethereal, temporary, and inconclusive. All too often full redress was fleeting as many judgments or settlements are never paid out. Workers often also found themselves in new jobs with yet another obstinate boss, and again having to confront whether it was worth again mobilizing, which would require renewed stress and uncertainty.

This pattern is true both for workers who process their individual claims through legal proceedings or administrative hearings, and for those who take more collective actions. Claims making processes fail not only because of weak labor law enforcement systems, but also because, in the words of one interviewee (an auto body repair shop worker) workers do not have the ability to “bear the weight of all of this.” The psychosocial stress of enduring workplace abuse and navigating the complicated and frustrating claims making processes strains and exhausts worker agency and reduces the long-term effectiveness of bottom-up strategies to reregulate the low-wage labor market. Many workers simply felt worn down.

Worker centers have become essential to addressing this waning energy for confronting the abuses of unfettered capitalism. Many organizers have adapted internal structures and strategies to engage workers for longer periods of time while mutual aid and leadership development activities build the kinds of supportive communities that can better sustain workers in their claims making processes. Philanthropies dedicated to building worker power must continue to support their work.

Low-wage workers, through worker centers and other alt-labor organizations, have won significant victories for workers against massive structural and institutional barriers. Yet, our findings also lead us to conclude that bottom-up workplace law enforcement is necessary but ultimately insufficient to alone reshape the low-wage labor market, to prevent workplace abuse, and to empower low-wage workers. The very nature of organizing is that it is difficult, it taxes worker agency, drains emotional resources, stresses psychosocial health, and exacerbates social conflict. The testimony of these workers is that without the strong bureaucratic machinery of state regulation and an overhaul of capitalist labor relations, we will continually mine ever-depleting resources of worker agency and collective action.

Read more

Jack Lesniewski and Shannon Gleeson. “Mobilizing Worker Rights: The Challenges of Claims-Driven Processes for Re-regulating the Labor Market” in Labor Studies Journal 2022.

Image: Project Luz via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

No Comments