The paradoxical promotion advantages of men in jobs dominated by women

Management promotions come with pay raises and a voice in workplace decisions. It is well-known that men receive promotions more often than women – but men’s promotion advantages relative to their female colleagues grow with the share of women in jobs. Therefore, men ride an invisible “glass escalator” that fast-tracks them into managerial promotions, especially in jobs that employ more women.

In a recently published paper, we ask: Is the glass escalator the same in all workplaces, or does it slow in workplaces predominantly employing women?

So far, research has studied the effect of gender composition on careers by looking at groups of jobs (as described above) or firms as a whole. However, understanding the combined effect of job and firm composition is essential because jobs typically exist within firms. Moreover, these two research areas come to opposite conclusions on the role of gender composition: While the glass escalator finds wider gender promotion gaps in jobs employing more women, the firm-level research finds more women managers in women-dominated firms.

When we distinguish between firms and jobs using unique employer-employee data, we find that the effect of job composition on gender promotion gaps strongly depends on the gender composition of the overall workplace. In answering our key question, data shows that the glass escalator slows down in women-dominated workplaces. The central mechanism driving this slowdown is the greater value attributed to women’s jobs (but not women per se) in women-dominated workplaces. Thus, instead of lifting all women’s boats, these workplaces only benefit women in women-dominated jobs.

Using administrative data to understand the effect of job and workplace gender composition.

So far, research has been unable to address how gender-specific effects of job composition depend on workplace composition because data connecting individual careers with workplace context was lacking until recently. We use German linked employer-employee data (LIAB) between 2012 and 2019 to overcome this limitation. These data include a representative sample of 8,500 workplaces in Germany, which respond to an annual survey describing their personnel practices and workforce composition.

The German Institute for Employment Research (IAB) combines the surveys with (anonymized) administrative employee records from all participating establishments. Employee data include basic information such as their gender, age, education, and occupation. Our analyses estimate the annual probability that an employee transitions to a managerial job, given they did not receive a managerial promotion before. We hold constant employee characteristics (e.g., their education, tenure), job characteristics (e.g., average years of education among job holders, numerical power of employee’s job compared to other jobs in the same workplace), and characteristics of workplaces (e.g., industry, gender composition of management, formalization of human resource practices).

The glass escalator slows down in women-dominated workplaces.

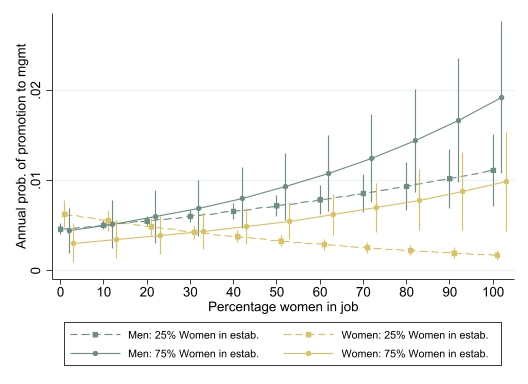

Our results show that the glass escalator in women-dominated jobs is most pronounced in workplaces primarily employing men. In contrast, the more women a workplace employs, the smaller gender promotion gaps become in women-dominated jobs (without ever closing completely). To provide a sense of these differences in gaps, we show our predicted annual promotion probability in Figure 1 and give an example of what these gaps actually look like over the span of seven years below.

On average, receiving a promotion takes seven years of tenure. Based on our regression, we predict the following difference in gender promotion gaps over the span of seven years, net of all controls. When women-dominated jobs (e.g., human resources) are located in women-dominated workplaces, nearly 10% of men transition to management within seven years, while only 5.3% of women do so. Thus, men’s cumulative probability of promotion to management in women-dominated establishments is nearly twice as high as their female colleagues.

Relative gender promotion gaps in women-dominated jobs (e.g., human resources) widen even more in establishments primarily employing men. Here, 6.4% of men transition to management within seven years, but only 1.5% of women, meaning men receive promotions four times faster than women.

Reconciling the job-based and firm-based gender composition literature.

As mentioned earlier, the glass escalator literature starkly contrasts with firm-based research. Our study resolves this paradox. Both bodies of literature were partially correct but ignored the role of changing job status.

Contrary to the expectation that all women are more valued as leaders in predominantly female workplaces, our data shows that women’s jobs (not women per se) are valued more in these environments. Consequently, more promotion opportunities go to women-dominated jobs when workplaces employ more women overall. Increasing job status weakens the glass escalator because women in women-dominated jobs (e.g., human resources) can use their job status to establish that they make capable leaders and narrow gender promotion gaps.

Because the glass escalator slows in women-dominated workplaces, women in women-dominated jobs reach leadership positions more often compared to the same jobs in workplaces dominated by men. Thus, the firm-based literature correctly observed that more women make it into management in more women-dominated firms. However, we highlight that this effect is produced by changing job status instead of a general appreciation of women in leadership. In fact, job status increases whenever job gender composition mirrors the workplace overall. Thus, it matters for women (but not men) whether their job and workplace gender composition match.

So, what does that mean for employers and workers?

These findings have implications for employers, who might miss important (female) talent in jobs that do not match the overall workplace composition– such as human resources in a tech company. Likewise, when women look for promotion opportunities, they need to target workplaces where the gender composition of their jobs matches the workplace. Specifically, women in women-dominated jobs (e.g., human resources) are best off in women-dominated workplaces. In contrast, women in men-dominated jobs (e.g., IT) should look for a company primarily employing men.

Authors:

Anne-Kathrin Kronberg is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and Organizational Science at UNC-Charlotte. She studies how organizations generate or alleviate race, class, and gender inequality through policies and practices.

Anna Gerlach is a research associate at Goethe University Frankfurt. She studies how welfare state and workplace policies shape women’s career opportunities and how these effects differ by education.

Markus Gangl is a Professor of Sociology at Goethe University Frankfurt. He studies economic inequality, labor markets, intergenerational mobility, and the role of public policies in shaping social stratification in affluent Western countries.

This research was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) grant number GA 758/5-1.

Read more:

Kronberg, Anne-Kathrin, Anna Gerlach and Markus Gangl “Promoting Men and Women to Management: Putting the Glass Escalator Paradox in the Establishment Context” in Social Science Research

Image: Thanh_Nguyen_SLQ via Pixabay.