A few years ago this blog ran a panel on ‘The future of organizational sociology’. In this panel renowned organizational scholars discussed the current position of organizational sociology as a field of research at a time when a large amount of organizational theory and research was developed and conducted at business schools. They argued that the future of the field could only be ensured if there were a continued discussion between sociologists based within these very different kinds of institution.

A few years ago this blog ran a panel on ‘The future of organizational sociology’. In this panel renowned organizational scholars discussed the current position of organizational sociology as a field of research at a time when a large amount of organizational theory and research was developed and conducted at business schools. They argued that the future of the field could only be ensured if there were a continued discussion between sociologists based within these very different kinds of institution.

Related debates on the future of organizational sociology and the direction of its development were published in the mid-1980s, for example by Robert Dingwall and Phil Strong and more recently by Patrick McGinty. These authors discussed the long-standing concern of interactionist research with organizations, the ‘negotiated order’ and with the ‘organizing of social life’. They looked for reasons for the neglect of this body of studies by those who, over the past 40 years or so, have developed organizational sociology in departments of sociology and in business schools.

Dingwall, Strong and McGinty argue that for a long time organizational sociology has been preoccupied with formal organizations and with the generation of concepts to aid its study, but that organizational sociologists have followed this interest at the expense of studying the contingencies and complexities of social actions that bring about organizational practices. In contrast to this, they point to the important contribution that interactionism has made to organizational sociology in its study of society as local practice (occurring in specific contexts) and situated practice (tied to specific instances of interaction).

Our book Institutions, Interaction and Social Theory follows on from these arguments by exploring in detail the connection between institutional scholarship and ‘interactionist’ research.

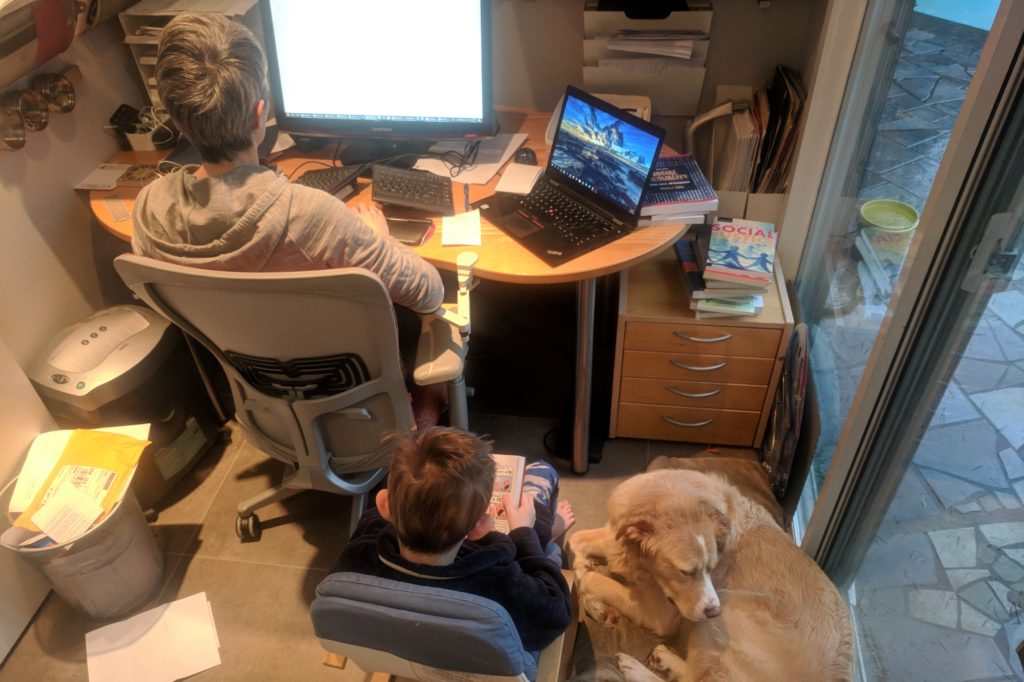

For many families, integrating work and care remains a challenge. Is flexible work the answer? By affording workers greater freedom to organize their jobs in ways that suit their lives, flexible hours and the ability to work from home can help parents meet children’s needs while still getting their work done.

For many families, integrating work and care remains a challenge. Is flexible work the answer? By affording workers greater freedom to organize their jobs in ways that suit their lives, flexible hours and the ability to work from home can help parents meet children’s needs while still getting their work done. Forget the red roses and teddy bears this Valentine’s Day – the best way for men to shore up their relationships is to run the vacuum over.

Forget the red roses and teddy bears this Valentine’s Day – the best way for men to shore up their relationships is to run the vacuum over.