The association between income and wealth is surprisingly complex and not well-understood. Yet this relationship is central to many of the questions that scholars of work, occupations, and inequality study.

The association between income and wealth is surprisingly complex and not well-understood. Yet this relationship is central to many of the questions that scholars of work, occupations, and inequality study.

The two are related but conceptually distinct: income is the flow of financial resources into a household from wages and salaries, investment returns, government transfer payments, and other sources. By contrast, wealth is a household’s total saved resources and is usually measured as net worth (total assets less total debts).

Both income and wealth are important measures of household financial well-being, the benefits a household receives from paid labor, and inequality across households. Not surprisingly, academics have rightfully studied both measures extensively; however, the association between income and wealth—beyond what each measure tells us on its own—holds additional and critical information that has attracted very little attention.

At first, the relationship between income and wealth may seem simple: as income increases, so too should wealth. Indeed, many assume that these indicators are strongly and positively correlated. In reality, the correlation between income and wealth is positive but relatively low, and there is no single, simple explanation for what happens to wealth when income rises.

The political homeownership ideal is the promise to create more equal and stable societies as well as to solve housing market problems by making more people homeowners, largely through the extension of mortgage credit to homebuyers. It also promises to fill the gap left by declining public housing and infrastructure investments and retrenching welfare states.

The political homeownership ideal is the promise to create more equal and stable societies as well as to solve housing market problems by making more people homeowners, largely through the extension of mortgage credit to homebuyers. It also promises to fill the gap left by declining public housing and infrastructure investments and retrenching welfare states. Compared with the increasing number of women entering male-dominated occupations, the number of men in female-dominated occupations remains very low. The male presence in typically female occupations has hovered at the levels observed in 1980, rising only slightly from 8 percent to 9.5 percent over the ensuing two decades.

Compared with the increasing number of women entering male-dominated occupations, the number of men in female-dominated occupations remains very low. The male presence in typically female occupations has hovered at the levels observed in 1980, rising only slightly from 8 percent to 9.5 percent over the ensuing two decades.

Many people enter occupations that require about the same level of education as they have, but some people enter occupations where their level of education exceeds the required level. Are these overeducated workers less happy with their work than other workers? We sought to answer this question in

Many people enter occupations that require about the same level of education as they have, but some people enter occupations where their level of education exceeds the required level. Are these overeducated workers less happy with their work than other workers? We sought to answer this question in

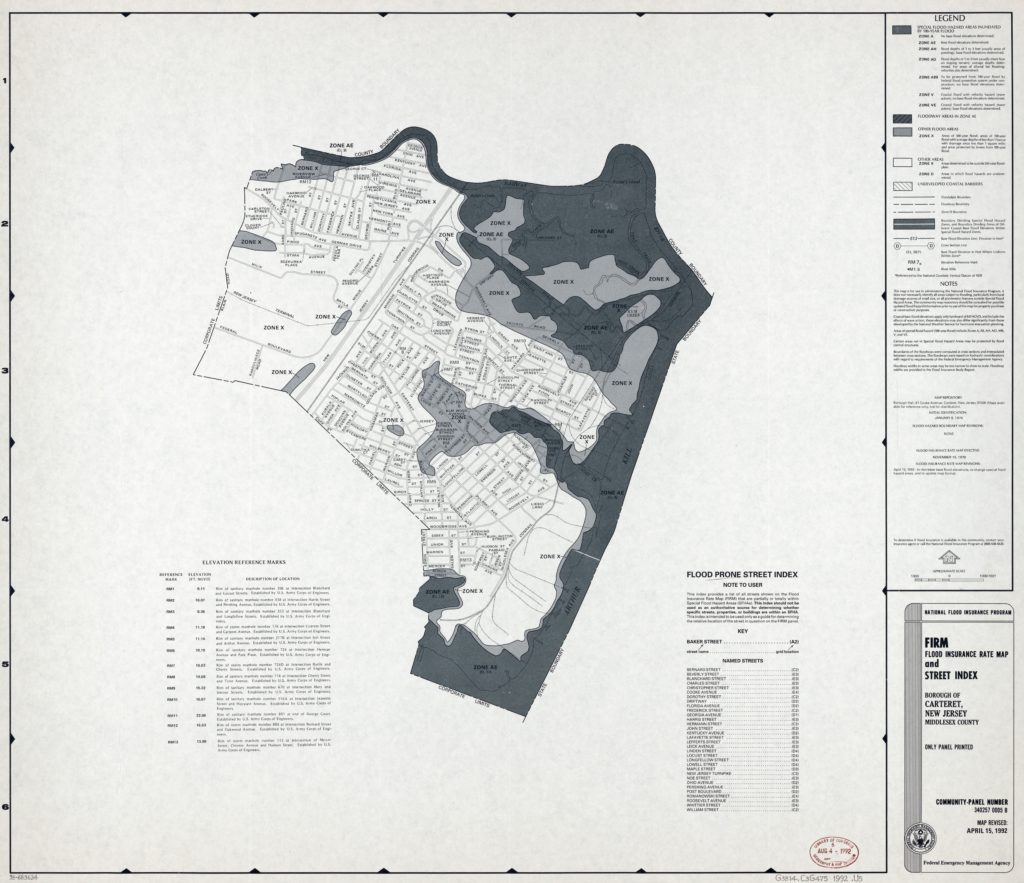

Climate change is making the planet we inhabit a more dangerous place to live. After the devastating 2017 hurricane season in the U.S. and Caribbean, it has become easier, and more frightening, to comprehend what a world of more frequent and severe storms and extreme weather might portend for our families and communities.

Climate change is making the planet we inhabit a more dangerous place to live. After the devastating 2017 hurricane season in the U.S. and Caribbean, it has become easier, and more frightening, to comprehend what a world of more frequent and severe storms and extreme weather might portend for our families and communities.