The current trend for fashionable post- and anti-work thinking has been given a boost by David Graeber’s book Bullshit Jobs, recently featured in an RSA event and accompanying video. Graeber’s critique of the modern world of work has been understandably popular and gained widespread media coverage. Stemming from a provocative piece in Strike magazine five years ago, the concept has spawned not just the book, but spin-off articles about the ‘bullshitization of academic life’, alongside similar efforts from others.

The current trend for fashionable post- and anti-work thinking has been given a boost by David Graeber’s book Bullshit Jobs, recently featured in an RSA event and accompanying video. Graeber’s critique of the modern world of work has been understandably popular and gained widespread media coverage. Stemming from a provocative piece in Strike magazine five years ago, the concept has spawned not just the book, but spin-off articles about the ‘bullshitization of academic life’, alongside similar efforts from others.

The bullshit job thesis (BJT) rests on two main claims. First that workers actually do hate their jobs or at least find no meaning or pleasure in them. The only reason we do such jobs are coercive effects of necessity and the work ethic. Secondly, as many as half of all jobs are ‘pointless’, have no social value and could be abolished without personal, professional or societal cost. The only reason they exist is for show, indicating that the boss has status or that time is being filled. The two claims are joined together by the view that, these ‘forms of employment are seen as utterly pointless by those who perform them’.

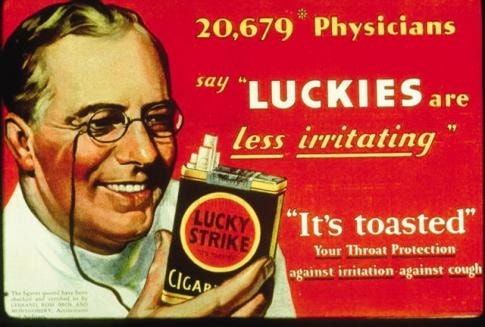

You’d have to be excessively hard hearted not to get some gratification from the BJT. Nobody likes managerialist jargon and telemarketers – as one of us should know, having worked the phones for four years in a past life. Plus, it’s not difficult to find humorous examples of people doing wasteful or daft tasks at work. But the two central claims of the BJT are an evidence-free zone. This is not the image promoted by Graeber and his fellow travellers. Much rests on an endlessly re-cycled 2015 YouGov poll, also reported by universal basic income enthusiast and author of Utopia for Realists Rutger Bregman, which showed that 37% of British workers think that their job doesn’t need to exist. The thing is, they didn’t say that at all. 37% said that their job didn’t ‘make a meaningful contribution to the world’. Well, that’s hardly surprising as that loaded question sets a very high bar. What is more surprising is that 50% said their jobs did make a meaningful contribution! The same poll found 63% found their job very or fairly ‘personally fulfilling’, while 33% did not. This non-bullshit outcome is entirely consistent with other evidence of high levels of work attachment. For example, the widely used longitudinal sampling of the Workplace Employment Relations Survey shows that, job satisfaction increased between 2004-2011 and that 72% were satisfied or very satisfied with ‘the work itself’, while 74% had a ‘sense of achievement’.

Stagnating wages among U.S. workers since the 1970s is well-documented. Also well-known is the outsized—and still growing—market impact of a small number of giant retailers such as Amazon.com Inc and Walmart Inc. What is less known is whether these two trends are linked.

Stagnating wages among U.S. workers since the 1970s is well-documented. Also well-known is the outsized—and still growing—market impact of a small number of giant retailers such as Amazon.com Inc and Walmart Inc. What is less known is whether these two trends are linked. In 2006,

In 2006, Job satisfaction matters. Of course, everyone would like to be happy with their work. But beyond that, scholars have also shown that job satisfaction is crucial for workers’ mental wellbeing and physical health, on the one hand, and important for employee performance and retention, on the other hand.

Job satisfaction matters. Of course, everyone would like to be happy with their work. But beyond that, scholars have also shown that job satisfaction is crucial for workers’ mental wellbeing and physical health, on the one hand, and important for employee performance and retention, on the other hand. High-involvement models of working are associated with high levels of worker influence over the work process, such as high levels of control over how to undertake job tasks or involvement in designing work procedures. We have recently published a review of the literature to find out what is known about the conditions that foster the adoption of such high-involvement models. We draw on studies of worker participation in management since the 1950s to explore what explains the dispersion of high-involvement work processes in the private sector.

High-involvement models of working are associated with high levels of worker influence over the work process, such as high levels of control over how to undertake job tasks or involvement in designing work procedures. We have recently published a review of the literature to find out what is known about the conditions that foster the adoption of such high-involvement models. We draw on studies of worker participation in management since the 1950s to explore what explains the dispersion of high-involvement work processes in the private sector.