“I’m sorry, but so and so’s brother needed to get hired. Shit happens,” Karen recounted, with resignation, a time her boss denied her a promotion.

Karen is a white woman who works at a hedge fund, a private financial firm. She continued, “When there’s big money, greed, power, people protect their own. And sometimes it’s the guy in the parish, the guy in the corner [office], the guy in the whatever.”

Karen’s account provides insight into why firms run by white men manage 97 percent of hedge fund assets—a $3.55 trillion industry. Moreover, she sheds light on why these elite men have amassed riches.

Indeed, I find that gender and racial inequality provide a key to explaining why hedge funds drive the divide between the rich and the rest. Since 1980, U.S. income inequality has skyrocketed, in part due to mushrooming pay in financial services. Hedge fund managers are well represented among the “1 percent” with average pay of $2.4 million. Even entry-level positions earn on average $372,000. ($390,000 is the threshold for the top 1 percent of families.)

It is difficult to overlook the growing number of reports and studies documenting the downward spiral of personal financial wellness within the United States. The

It is difficult to overlook the growing number of reports and studies documenting the downward spiral of personal financial wellness within the United States. The  By the end of this month, the Internal Revenue Service will have

By the end of this month, the Internal Revenue Service will have Compared to other workers, mothers face a number of disadvantages, including lower wages, bias in recruitment and promotion, and a greater risk of joblessness. These disadvantages may be more prevalent in professional jobs where ‘ideal worker’ norms are most salient. Professional employers tend to view mothers as less competent and committed than other workers—a major stigma in careers that require around-the-clock dedication.

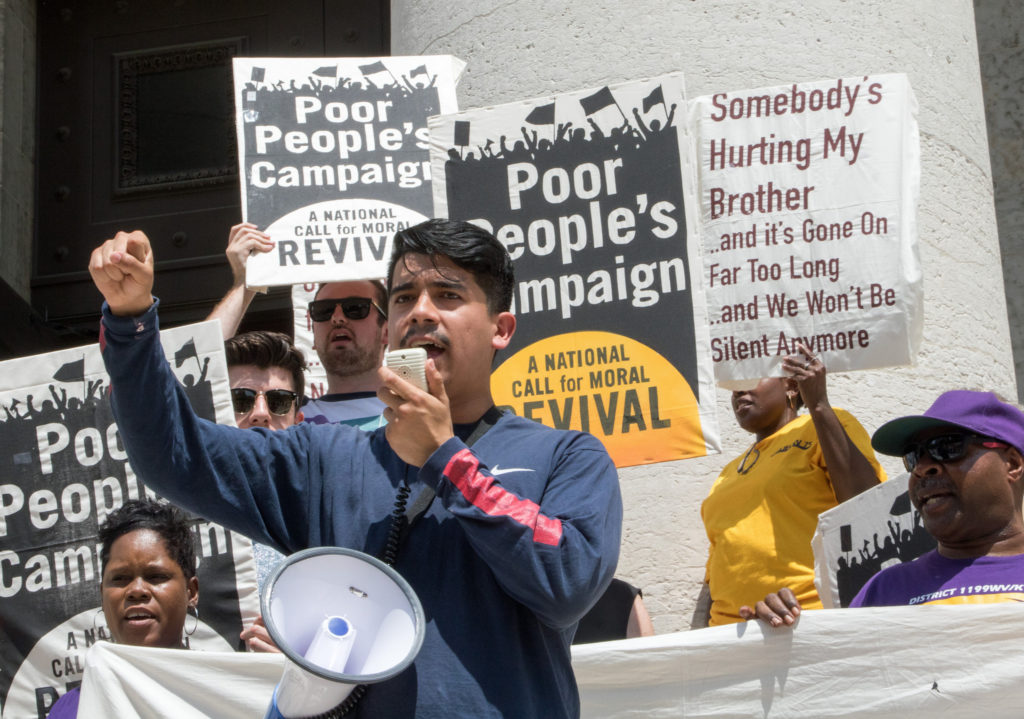

Compared to other workers, mothers face a number of disadvantages, including lower wages, bias in recruitment and promotion, and a greater risk of joblessness. These disadvantages may be more prevalent in professional jobs where ‘ideal worker’ norms are most salient. Professional employers tend to view mothers as less competent and committed than other workers—a major stigma in careers that require around-the-clock dedication. Fifty years after the civil rights movement, racial economic inequality remains a major fact of American life. In fact, the gap in family income between blacks and whites has been almost perfectly constant since the 1960s.

Fifty years after the civil rights movement, racial economic inequality remains a major fact of American life. In fact, the gap in family income between blacks and whites has been almost perfectly constant since the 1960s. The current trend for fashionable post- and anti-work thinking has been given a boost by David Graeber’s book

The current trend for fashionable post- and anti-work thinking has been given a boost by David Graeber’s book